Perhaps it’s not so very strange to find parallels between C.S. Lewis the [former] atheist and today’s ‘new atheists’. Lewis’s career overlapped with that of highly influential Oxford atheists such as A.J. Ayer, Antony Flew, Gilbert Ryle and P.F. Strawson, as well as that of the Cambridge-educated philosopher Bertrand Russell; figures who taught, supervised or otherwise influenced the likes of Daniel Dennett and A.C. Grayling. Today’s neo-atheists continue to be enamoured of ‘what we might loosely call the Scientific Outlook, the picture of Mr [H.G.] Wells and the rest’, as Lewis once put it. Indeed, in 1924 Lewis noted that ‘in [Bertrand Russell’s essay] “Worship of a Free Man” I found a very clear and noble statement of what I myself believed a few years ago.’ According to Russell:

That man is the product of causes which had no prevision of the end they were achieving; that his origin, his growth, his hopes and fears, his loves and his beliefs, are but the outcome of accidental collocations of atoms; that no fire, no heroism, no intensity of thought and feeling, can preserve an individual life beyond the grave; that all the labours of the ages, all the devotion, all the inspiration, all the noonday brightness of human genius, are destined to extinction in the vast death of the solar system, and that the whole temple of Man’s achievement must inevitably be buried beneath the debris of a universe in ruins—all these things, if not quite beyond dispute, are yet so nearly certain, that no philosophy which rejects them can hope to stand. Only within the scaffolding of these truths, only on the firm foundation of unyielding despair, can the soul’s habitation henceforth be safely built.

Today’s neo-atheists are of course building their lives upon the same scaffolding (much of which can be traced back to Scottish sceptic David Hume, whose writing Lewis much admired). Some build with the same attitude of nihilistic ‘true grit’ that once attracted Lewis. Thus William B. Provine writes as what Lewis called ‘a consistent pessimist’, stating: ‘There are no gods, no purposes, and no goal-directed forces of any kind. There is no life after death. When I die . . . That’s the end of me. There is no ultimate foundation for ethics, no ultimate meaning in life, and no free will for humans, either.’ Peter Atkins likewise affirms that (from his naturalistic perspective) when the sun dies: ‘We shall have gone the journey of all purposeless stardust, driven unwittingly by chaos, gloriously but aimlessly evolved into sentience, born unchoosingly into the world, unwillingly taken from it, and inescapably returned to nothing.’

Others build upon Russell’s scaffolding with what Richard John Neuhaus calls a ‘debonair nihilism’, an existential determination to ignore the meaninglessness of it all by enjoying the subjective bloom of the metaphorical roses along life’s way. Hence, although Richard Dawkins agrees with Steven Weinberg’s comment that ‘the more the universe seems comprehensible, the more it seems pointless’, he nevertheless wants ‘to guard against . . . people therefore getting nihilistic in their personal lives.’ Dawkins argues (correctly) that subjective human purposes lacking objective value are compatible with an objectively meaningless cosmos: ‘You can have a very happy and fulfilled personal life even if you think the universe at large is a tale told by an idiot. You can still set up goals and have a very worthwhile life and not be nihilistic about it at a personal level.’ Likewise, A.C. Grayling affirms that ‘the meaning of your life is the meaning you give it.’ But this is at best a pyrrhic victory over meaninglessness (and one only available to those capable of exercising such existential intentionality). As Terry Eagleton observes, humans are contingent beings who depend both upon nature and each other:

whatever [subjective] meaning I may forge for my own life is constrained from the inside by this dependency. We cannot start from scratch. It is not a matter of clearing away God-given meanings in order to hammer out our own, as Nietzsche seemed to imagine. For . . . we are woven through by the [subjective] meanings of others–[subjective] meanings we never got to choose, yet which provide the matrix within which we come to make sense of ourselves and the world. In this sense . . . the idea that I can determine the [subjective] meaning of my own life is an illusion.

Even if the idea that I can determine the subjective meaning of my life weren’t an illusion, the determination of subjective meaning can never deliver more than the self-deluded illusion of objective meaning. As French atheist André Comte-Sponville concludes: ‘there is no way for a lucid atheist to avoid despair.’

Dawkins likes to talk up the emotional rewards of science: ‘All the great religions have a place for awe, for ecstatic transport at the wonder and beauty of creation. And it’s exactly this feeling of spine-shivering, breath-catching awe—almost worship—this flooding of the chest with ecstatic wonder, that modern science can provide.’ However, given Russell’s scaffolding, such value-laden terms as ‘awe’ and ‘beauty’ refer to nothing but subjective personal reactions taking place within, and relative to, by-products of an evolutionary process lacking any intrinsic meaning or given purpose. In the final analysis, Dawkins affirms that ‘the universe we observe has precisely the properties we should expect if there is at bottom no design, no purpose, no evil and no good, nothing but pitiless indifference.’ As Lewis held (both as an atheist and a Christian): ‘Either there is significance in the whole process of things as well as in human activity, or there is no significance in human activity itself . . . You cannot have it both ways. If the world is meaningless, then so are we . . .’ Thus Lewis explained that when he accepted Russell’s naturalistic worldview: ‘The two hemispheres of my mind were in the sharpest contrast. On the one side a many-islanded sea of poetry and myth; on the other a glib and shallow “rationalism”. Nearly all that I loved I believed to be imaginary; nearly all that I believed to be real I thought grim and meaningless.’

— Peter S. Williams is Assistant Professor in Communication and Worldviews at Gimlekollen School of Journalism and Communication, NLA University College, in Norway. For Peter's podcast, YouTube channel, and other resources, visit peterswilliams.com.

This passage is excerpted from Peter S. Williams, C. S. Lewis vs. the New Atheists (Paternoster, 2013).

Image by press 👍 and ⭐ from Pixabay

Notable Deals

Logos is running a Christmas sale with lots of great deals on the newest version of the software (Logos 9), commentaries, books, lectures, and other resources.

Look here for Faithlife’s free eBook of the Month. Visit here to get the Logos Free Book of the Month. You can download the free version of Logos which will allow you to access the monthly free books. Logos 9 is a great investment, though, and has tons of tools that make Bible study easier and richer.

Save up to 70% on commentaries from Lexham Press, while supplies last.

Receive a free trial subscription to Zondervan’s MasterLectures. They have lots of great lectures available from leading evangelical scholars. You can listen to or watch the videos on your computer or phone, or on your TV through Apple TV, Roku, Amazon Fire TV, and Android TV.

Recommended Resource

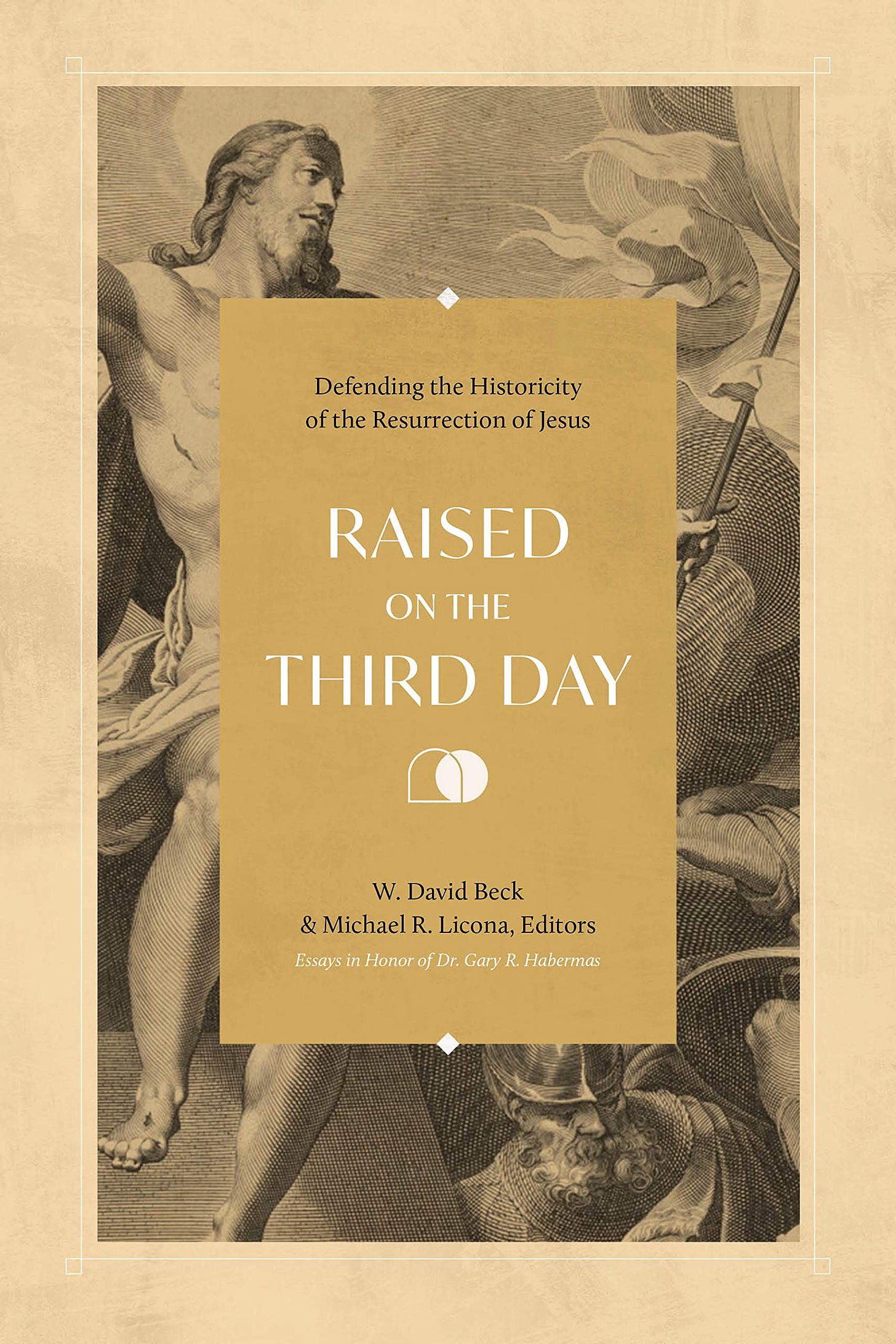

One of the key pillars of the Christian worldview is the resurrection of Jesus Christ from the dead. As the apostle Paul wrote, “if Christ has not been raised, our preaching is useless and so is your faith” (1 Cor. 15:14). Thus, defending the resurrection has always been one of the chief tasks of apologetics, and one that requires ongoing development as new evidence, fields of study, and objections emerge.

Raised on the Third Day: Defending the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus brings together some of the most notable Christian scholars who have defended the resurrection, including J. P. Moreland, William Lane Craig, Craig Evans, and Darrell Bock. The essays are written in honor of Gary Habermas, one of the foremost defenders of the resurrection in our generation. With chapters on the minimal-facts argument, near-death experiences, the uniqueness of Christianity, historical epistemology, and lessons for apologists from Habermas’s ministry, these essays provide a snapshot of some of the best available scholarship on the resurrection.

The excerpt below is taken from Alex McFarland’s chapter “What Aspiring (and Veteran) Apologists May Learn from Gary Habermas.”

What Aspiring (and Veteran) Apologists May Learn from Gary Habermas

To be sure, Gary Habermas has shaped the lives of countless people, my own included. Habermas’s accomplishments as an academic, an apologist, and as a Christian public figure are notable. His scholarship about ancient evidence for the life of Christ, near-death experiences, dealing with doubt, or his “minimal facts” defense of the gospel are all significant. Equally compelling has been the Christ-honoring way in which he processed the loss of his wife, Debbie.

As pop-level atheism became a cottage industry in the early 2000s, the skeptic’s world was rocked when news broke that one of their champions, Antony Flew, affirmed theism. Habermas’s lengthy friendship and dialogues with Flew decisively contributed to this. And how many apologists get written into the scripts of theatrically released feature films? Factor in the significant role he has played in Lee Strobel’s journey, and it becomes clear that Habermas is one of the persons most used by God to raise awareness for apologetics over the last two decades.

But what I’ve learned about apologetics from Gary Habermas goes well beyond refutations of naturalistic theories about the resurrection.

So often, apologetics is assumed to be a pastime of intellectual jousting that takes place among bookish believers. Even many pastors and Christian educators (who would, presumably, be favorable toward apologetics) can be dismissive of this realm of study. “You will never need that C. S. Lewis stuff,” a senior denominational leader once said to me, “unless you are on the campus of Yale University. Islam, atheism, trying to prove the Bible—those issues the average believer will never deal with.”

That person’s low view of apologetics was especially ironic in light of the fact that issues he referenced (Islam, atheism, the authority of Scripture) are, in fact, exactly the topics Christians in the Western world must know how to address. Some complain, “You can’t argue someone into the kingdom of God,” or, “Apologetics may help reassure believers, but it doesn’t win the lost to Christ.” I am mindful of the fact that some in the church have not had unfavorable experiences with apologetics, but rather negative encounters with apologists.

Once, while encouraging a group of ministers to bring more apologetics and biblical worldview content before their people, one pastor shared a story that broke my heart. The pastor explained that a two-person apologetics team had come to the church to speak to their youth. During the Q&A time, a teen girl innocently asked a question about Jehovah’s Witness literature that had been coming to her house. She said she had been reading their Awake magazine, and to her it seemed to make sense. “What do you guys think?” she asked.

The two young men (perhaps well-meaning but misguided) launched into a rapid-fire rebuttal of everything related to the Jehovah’s Witnesses. As her youth group friends watched, the speakers did a five-minute “data dump” on the girl, critiquing both the publications and her for having read them. The pastor grew fairly emotional as he ended the story: “Alex, that teen girl was so embarrassed that she left the room crying. The worst part is that the two apologists seemed to show no concern, and they high-fived each other at the end of their talk.”

That encounter illustrates how the apologetics and life of Gary Habermas remains so exemplary. The pastor’s experience still makes me cringe whenever I think back on it. I agreed with him that the behavior described typifies a sort of apologetics that should never be encouraged. But Christian friend and ideological foe alike will agree that Gary Habermas, the man, is undeniably a credit to the worldview he represents. Habermas proclaims truth; better still, he lives it.

I am reminded of a time that Habermas presented his “minimal facts” argument before hundreds of students at the University of North Carolina, Charlotte.

The standing-room-only crowd listened intently as a long line formed for the Q&A period. In characteristic fashion, Habermas fielded comments, objections, and helped more than a few students who did not quite know how to frame their question. One young man came to the mic and made it clear that he did not like the conclusions Habermas drew from the implications of Christ’s physical resurrection.

“If I’m understanding you,” the student reasoned, “the resurrection would mean that Jesus is God, and the way of salvation.” The young man’s tone grew belligerent: “Is that what you’re saying?”

“You got it,” said Habermas. “You are tracking with me, yes.”

The college student appeared more and more agitated as it sunk in that the resurrection would, indeed, validate Christ’s messiahship. His volume rising, the student said, “I don’t like this! I don’t like this!” Half the audience seemed to want the aggrieved student to step aside, and half seemed bemused to watch the meltdown in process. Habermas offered, “I get it, you’re not comfortable with where this is going. But just to say that you don’t like it, well, that’s not an argument.”

Amazingly, the student waved his hands, as if to say, “Be gone!” to both Habermas and his content. Storming away, the young man growled into the mic, “AARRRGGHHH!” Some snickered at the exchange, and the program concluded. But I watched Gary Habermas seek out the young man, who clearly had no idea he was trying to argue the resurrection with the topic’s most astute scholar. It was a powerful sight to watch Habermas, like a gentle big brother, listen to the student, diffuse the young man’s anger, and minister the gospel. Apologetics comprises both scholarship and shepherding.

Find Raised on the Third Day: Defending the Historicity of the Resurrection of Jesus at Lexham Press or Amazon.

* This is a sponsored post.

Subscribe, and Get a Second Subscription Free!

From now until the end of the year, subscribe to The Worldview Bulletin for only $2.50 per month, and receive a second year-long subscription for a friend, free!

After subscribing, simply send their email address to worldviewbulletin@gmail.com, and we’ll set it up (please make sure you have their permission first).

As a subscriber, you’ll receive a year’s worth of equipping, encouragement, and resources for understanding and defending the Christian worldview, written by some of today’s leading scholars and apologists. You’ll also support our work of providing these resources to believers everywhere.