December Issue of The Worldview Bulletin-Pt. 1

Monism and Pantheism | The Argument from Damnation

Greetings! We hope the new year is off to a good start for you. In this first edition of the Bulletin in 2022, Paul Copan continues his series on worldviews and explains the philosophical question of “the one and the many,” and how the opposing worldviews of monism and pantheism respond. Melissa Cain Travis sketches an argument from damnation in light of horrendous human evil. David Baggett continues his series on the ethical dimensions of epistemology and how this is illustrated in C. S. Lewis’s novel Till We Have Faces. Paul Gould concludes by suggesting a number of ways that a theistic account of nature is superior to the prevailing anthropocentric view. As usual, we also collect important news, along with deals on books and resources.

Happy New Year!

Christopher Reese

Editor-in-Chief

Contents

Part One

Questioning Worldviews: Part 3

Monism and Pantheism 1:

The One and the Many

by Paul Copan

The Argument from Damnation, Part 1

by Melissa Cain Travis

Please see the second email for Part Two of the newsletter.

Questioning Worldviews: Part 3

Monism and Pantheism 1: The One and the Many

by Paul Copan

Introduction

Have you ever thought of the remarkable philosophical and theological fruitfulness of the doctrine of the Trinity? Within the Godhead exists a threeness of persons and oneness of nature and being. We have differentiation within unity, but without contradiction. To illustrate the Trinity, some Christian thinkers have used the analogy of Cerberus, the Greek mythological three-headed dog. Cerberus has three distinct centers of awareness or consciousness as well as oneness of being (it’s one dog, not three) and nature (just one canine nature possessed by each center of awareness). Perhaps we ignore or take for granted this rich doctrine and the remarkable clarity and explanatory power it brings. We’ll come back to the doctrine of the Trinity next month, but for now, I want to introduce the discussion of the one and the many.

The pragmatist philosopher William James (1842-1910) said that the problem of the one and the many—the relationship of unity and differentiation—has been a central question in the history of philosophy.[1] Indeed, in my Fall 2021 History of Philosophy class in PBA’s new MA Philosophy of Religion program, I discussed this theme with my students.

In my current series that examines various worldviews (we’ve covered Deism and existentialism, so far), I’ll look at the related themes of monism (all reality is an undifferentiated oneness) and pantheism (all things are divine). As it turns out, these are two distinct schools within philosophical Hinduism but they are also illustrated in pre-Socratic philosophy. In the first part of my discussion of monism and pantheism, I’ll discuss these concepts as they relate to (a) the pre-Socratic philosophers and then (b) philosophical Hinduism.

Pre-Socratic Philosophers

The Many (Heraclitus)

The problem of the one and the many is nicely illustrated in the history of philosophy prior to the time of Socrates (470-399 BC). Some pre-Socratic philosophers like Empedocles (495-435 BC) and Anaxagoras (500-428 BC) claimed that reality is comprised of qualitatively distinct elements, though these thinkers disagreed about the precise number of these fundamental components of reality. Empedocles believed that reality was comprised of four necessary particles: solid (earth), liquid (water), air (gas), and heavenly matter (fire). This raised the inevitable question: what, if anything, unites or gives these different particles? Here we come to the word quintessential (which for many is just a fancy way of saying “essential”): what is the unifying fifth element or essence—the “quintessence”?

Perhaps the most noted ancient philosopher who emphasized the many was Heraclitus, from Ephesus (535-475 BC)—the one who said one could not step into the same river twice. He asserted: “All things are in a state of flux [panta hrei].” Physical reality involves many entities that are constantly changing.

Now, Heraclitus did believe in an impersonal version of “God”—similar to the view of God held by the later Stoics: “To God all things are fair and good and right, but men hold some things wrong and some things right.” He, like the Stoics, was a pantheist (everything is God), but he believed in a distinction between reason and matter. (We could call this metaphysical dualism.)

But for those pre-Socratics who affirmed the fundamental reality of the many or multiplicity, we can ask: what unifies distinct categories, elements, or things? In our own day, we could say this about postmodernism—a diversity or multiplicity of narratives or perspectives exists without anything to unify them (a metanarrative).

The One (Parmenides)

A philosopher who emphasized the oneness of reality was Democritus (560-370 BC). All reality is comprised of matter (monism). He held that external elements are ultimately the same but come in different forms. The only difference between things is just the size, weight, and arrangement of their atoms.

The most noted monistic pre-Socratic Greek philosopher was Parmenides (born either 540 or 515 BC). He claimed that plurality and distinction don’t exist. Ultimate reality is one and unchanging. Therefore, any change and transition are illusory. What’s more, sense perception as a means of knowledge is unstable and deceptive. Being is; becoming is impossible—an illusion. Being is all the reality that there is, and continues to exist changelessly. Parmenides believed that all reality was material (monism), but, even so, sense perception is unreliable—it yields mere appearance. One must utilize reason to understand this.

Plato would pick up on this theme, siding with Parmenides against Heraclitus. However, Plato rejected Parmenides’s materialism. Rather, he anchored knowledge in the stable and eternal realm of the forms—the objects of true knowledge.

Philosophical Hinduism

The actress Shirley MacLaine claimed to have gotten to the bottom of the human problem—namely, the “tragedy of the human race was that we had forgotten that we were each Divine. You are everything. Everything you want to know is inside of you. You are the universe.”[2] If only we remembered our divinity—or even what we had learned in past lives—the human condition would be much improved.

Such an idea is a modern iteration of what the ancient Hindu Upanishads affirm: the self or soul (atman) is identical with God, the Ultimate Reality (Brahman). Here are a few statements to that effect:

· “All this is Atman.”[3]

· “Atman is being known. . . . everything is known.”[4]

· “This self is the Brahman.”[5]

· “I am Brahman.”[6]

The Hindu Upanishads tell the story of a boy who is told by his father to cut open a fruit and then its seeds, which are empty inside. The father tells him: Tat tvam asi: “That thou art.” The interpretation of this cryptic statement is that the individual has no distinct identity. The soul is “God”—a type of monism; that is, all reality is an undifferentiated oneness. Any real difference does not exist but is illusory (maya). So to believe that more than one reality exists is like claiming that a wrinkle in a carpet is different from the rest of the carpet.

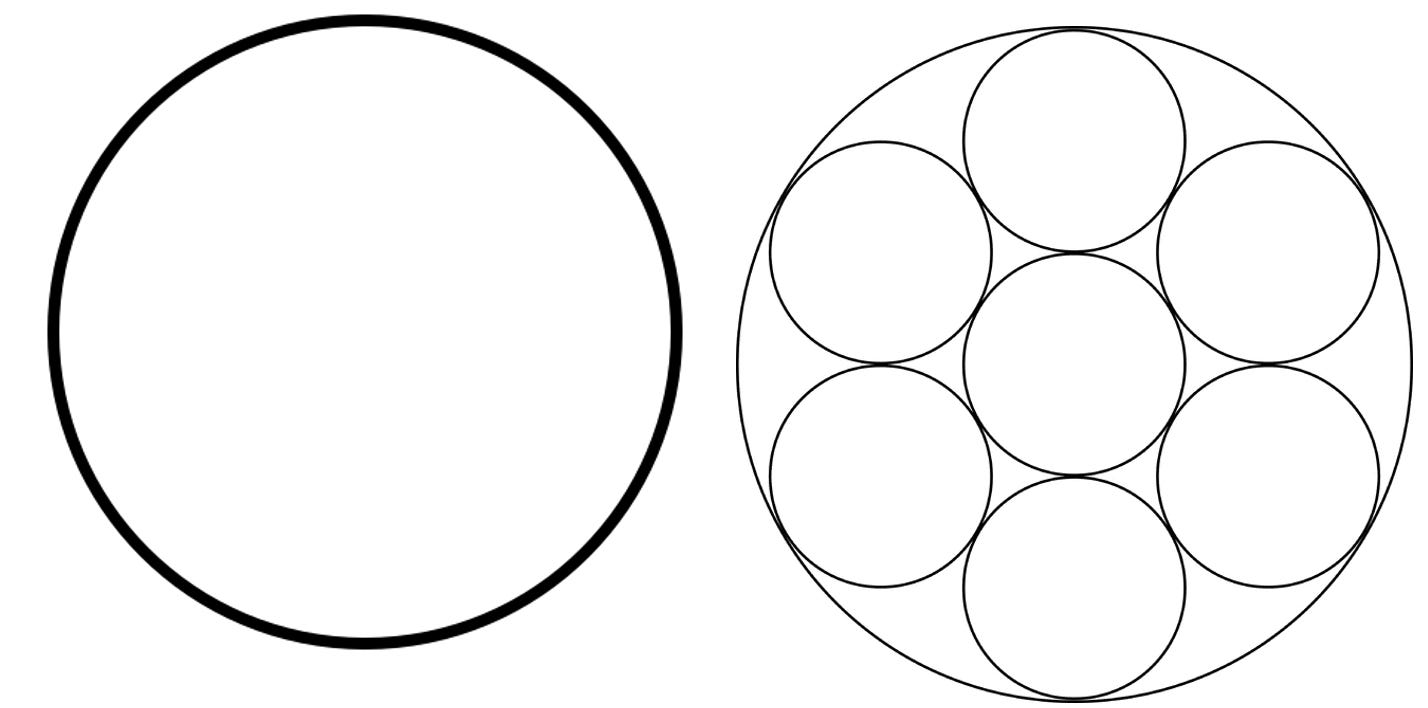

By contrast, pantheism affirms real distinctions between things, but all of those distinct things are all part of God: the Taj Mahal, pepperoni pizza, you, and I. To illustrate, think of monism as representing a circle with nothing inside it. By contrast, the circle with smaller circles within it illustrates pantheism—that the one (“God”) is comprised of many things.

Below we discuss two Hindu philosophers who illustrate these distinct (!) viewpoints.

Shankara—No Differentiation (Monism)

The Hindu philosopher Shankara (d. 820), whose monism represents the Advaita Vedanta school of Hinduism, emphasized that theme from the Upanishads. This is a view called nirguna Brahman: no differences/no qualities (nirguna) exists; only Brahman (God) exists.

Just reflect on your own experience of consciousness: you think about objects of perception—like tables, chairs, trees, and stones; you feel different emotions; you intend to carry out your to-do list for the day; you reason your way to certain conclusions; you reject ideas you take to be false. Now strip all of these distinctions away from your thinking. “Go blank” in your thinking. All you are left with is a state of pure consciousness or awareness. That is what is meant by “God.” God just is this pure undifferentiated awareness. There is no difference between you (a self) and this ultimate reality.[7]

Shankara maintained that the Absolute (Brahman) understood accurately has no qualities (nirguna). To think about distinctions or qualities (saguna) is to think about a lower level of reality, but this is inaccurate. Brahman is neti neti (“not this, not that”). So the many gods of India aren’t real but are ultimately illusory (maya).

Over a millennium later (1893), at the World Parliament of Religions in Chicago, Swami Vivekenanda proclaimed this doctrine—that the misery in our world is the result of making distinctions:

Where is there any more misery for him who sees this Oneness in the Universe, the Oneness of life, Oneness of everything? This separation between man and man, man and woman, man and child, nation from nation, earth from moon, moon from sun, this separation between atom and atom, is the cause really of all this misery, and the Vedanta says this separation does not exist; it is not real. It is merely apparent, on the surface. In the heart of things there is unity between man and man, women and children, races and races, high and low, rich and poor, the Gods and man: all are One, and animals too if you go deep enough, and he who has attained to that has no more delusions.

Ramanuja—Differentiation (Pantheism)

The Hindu philosopher Ramanuja (d. 1137) rejected this undifferentiated oneness espoused by his predecessor. He claimed that differences exist (saguna), but they are all part of Brahman. This is “pantheism”: all (pan) is God/divine (theos). Ramanuja believed that the cosmos was without origin but ever-dependent upon Brahman. He rejected nirguna Brahman in favor of saguna Brahman. The deities of India aren’t illusory. Although everything is God, there are differences within God. So for Sankara, differentiation is the essence of ignorance. For Ramanuja, differentiation is actually the basis for knowledge.[8]

In the next issue of the Worldview Bulletin, I’ll offer a response to pantheism and monism as well as draw together some of the strands concerning the “one vs. the many.”

Notes

[1] William James. “The One and the Many,” Lecture 4 in Pragmatism: A New Name for Some Old Ways of Thinking (New York: Longman Green and Co., 1907), 49-63.

[2] Out On a Limb (New York: Bantam, 1983), 347.

[3] Chandogya Upanishad 7.52.2.

[4] Brihadaranyaka Upanishad 4.5.6.

[5] Ibid., 2.5.19.

[6] Ibid., 1.4.10.

[7] Robin Collins, “Eastern Religions,” in Michael Murray, ed., Reason for the Hope Within (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1999), 187. Collins’ chapter offers a concise perspective on and critique of Eastern religion.

[8] For a helpful discussion on this, see Timothy C. Tennent, Christianity at the Religious Roundtable (Grand Rapids: Baker, 2002), 37-61.

— Paul Copan is the Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Learn more about Paul and his work at paulcopan.com.

Image by Gerd Altmann from Pixabay

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to The Worldview Bulletin Newsletter to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.