Evil Exists; Therefore, God Exists

By Paul Copan

Greetings! We hope everyone is staying safe in the midst of the coronoavirus chaos. We hope you enjoy this bonus article from the recently released March issue of The Worldview Bulletin. In this third part of Paul Copan’s series on the problem of evil, he examines the definition of evil, and sketches an argument for God’s existence on the basis of evil. As an added bonus, we’re also including our list of free and discounted books and other resources—good for these days of extended time indoors.

Blessings,

Christopher Reese

Managing Editor

Walking Away from God Because of Evil, Part 3: Defining Evil

by Paul Copan

Recapping

As you recall from the last issues of the Worldview Bulletin, the backdrop to my discussion on evil goes back to an exchange I had with a Colorado pastor a couple of years ago. He had shared with me how the kidnapping, rape, murder, and dismemberment of a ten-year-old girl in his congregation rocked his church. The devastated mother of the girl said that she couldn’t believe in a God who would allow this horrendous evil to happen to her innocent daughter. The baffled pastor felt that he, as a Christ-follower, had no real resources to offer and that he even should step down from leadership. He reached out to me, hoping for some reason to stay in the ministry.

Now, in this series, we are pointing out some of the rich resources the Christian faith offers as we face the baffling problem of profound evil in the world. And we’ve noted that one of the relevant questions to ask is this: Which worldview or philosophy of life offers us the best resources for addressing the problem of evil? We’re not asking which worldview answers all questions concerning evil—simply, which one best addresses them.

Last month we observed that, unlike certain worldviews such as versions of Eastern monism, Christian Science, or strict naturalism, the Christian faith takes the problem of evil very seriously. The gospel does not consider evil illusory or dismiss evil as mere “bad luck” or something we don’t like. But this “bad luck” view of evil has come to dominate the landscape of modernity. Susan Neiman states in her book Evil in Modern Thought that, prior to the Lisbon earthquake (1755), events such as this (and we could add the coronavirus) were considered morally and theologically significant. Yet the tendency in our modern era has been to treat these events as strictly natural phenomena: “For contemporary observers, earthquakes are only a matter of plate tectonics. They threaten, at most, your faith in government building codes or geologists’ predictions. They may invoke anger at lazy inspectors, or pity for those stuck in the wrong place at the wrong time. But these are ordinary emotions.”[1] But surely evil involves something deeper. Shall we dismiss as mere misfortunes events like the Holocaust or the Ukrainian Holodomor (from which my own paternal grandfather died)?

As we move on from the matter of acknowledging the reality of evil, we come to the very definition of evil.

Defining Evil

If a good God does not exist, what is the alternative? One competing worldview is naturalism, which claims that we find ourselves in a materialistic world—with humans being “a collection of … molecules” (Carl Sagan) or “collocations of atoms” (Bertrand Russell). But if this is so, how can we begin to make sense of evil? By what standard do we judge something to be evil?

My Christian philosopher friend Doug Geivett has observed it is the theists—not the atheists or naturalists—who are more likely to offer definitions of evil. These non-theists, who wield the argument from evil against God’s existence, more often tend to assume the reality of evil than actually define it. But, Geivett argues, the very definition of evil—a departure from the way things ought to be—presumes a kind of standard, blueprint, or design-plan of the way things ought to be.[2] As Neiman notes, when we say, “this ought not to have happened,” we are moving to the topic of the problem of evil.

When C. S. Lewis was an atheist, one of his objections to God was that evil existed. How could God exist given all the injustices in the world?

My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust? . . . Thus in the very act of trying to prove that God did not exist—in other words, that the whole of reality was senseless—I found I was forced to assume that one part of reality—namely my idea of justice—was full of sense.[3]

Lewis assumed a measuring rod by which he was able to judge something as evil. The very definition of evil points us to a standard, from which there is a deviation.

Dualism and Evil

Perhaps we’ve encountered this claim: “We need evil to understand what goodness is, and we need goodness to make sense of evil.” It pronounces the necessary coexistence of evil and goodness. Now, this may seem reasonable at first glance, but what are we to make of it? To get something of a philosophical foothold, consider the phenomenon of counterfeit money. Surely we wouldn’t say, “We need counterfeit money to account for authentic currency, and we need authentic currency to make sense of counterfeit money.” No, genuine legal tender can exist without counterfeit money, but counterfeit money makes no sense—and no cents for that matter!—without genuine currency. Evil is parasitic on goodness.

Contrary to the dualism of the ancient Manichees, whose creed affirmed an eternal duel-ism between good and evil—we recognize the more fundamental reality of goodness by which we judge something to be evil. Goodness is prior to evil. There is no eternal struggle between the two. This is certainly the case with the biblical metanarrative—a supremely good God existed and made a “very good” creation. Goodness existed without evil. Furthermore, we intuitively recognize that goodness—or, if you like, a design-plan—is prior to evil. For example, in books and films, we cheer for the “good guys” to overcome evil. And in real life, we hope that goodness will prevail, that evil will be vanquished, that justice will be done, and that even something beautifully redemptive can emerge from horrendous evil.

In the movie The Fellowship of the Ring, When Frodo tells his faithful friend Samwise Gamgee, “I can’t do this, Sam,” Sam tries to put into perspective Frodo’s daunting task of bringing the ring to the fires of Mount Doom:

I know. It’s all wrong. By rights we shouldn’t even be here. But we are. It’s like in the great stories, Mr. Frodo—the ones that really mattered. Full of darkness and danger, they were. And sometimes you didn’t want to know the end. Because how could the end be happy? How could the world go back to the way it was when so much bad had happened? But in the end, it’s only a passing thing, this shadow. Even darkness must pass. A new day will come. And when the sun shines, it will shine out the clearer. Those were the stories that stayed with you—that meant something—even if you were too small to understand why.[4]

Naturalism and Evil

According to the naturalist, nature is all the reality there is. But naturalists come in two basic varieties. Some could be classified as “broad” naturalists. They believe in objective moral values (including the reality of evil), human dignity and worth, beauty, (self-)consciousness, moral responsibility/freedom, and so on. We won’t comment on this view much beyond saying that it looks a lot like theism—though without God, of course, and also without the relevant metaphysical background to produce such goods: value from valuelessness, consciousness from non-conscious matter, freedom from deterministic processes, and so on.

The “strict” naturalists, by contrast, are the more consistent of the two. They hold to three basic tenets: materialism (matter is the only reality); determinism (each event is the necessary result of prior physical forces); and scientism (science alone furnishes us with knowledge). Though we can’t explore the pillars of naturalism here, we can say that this stark version ultimately strips humans of all the things we typically associate with our humanity: dignity, morality, self-awareness, personal responsibility, beauty, imagination, and so on. To embrace naturalism is to reject the most fundamental things we know about ourselves. As the naturalistic philosopher Jaegwon Kim acknowledges, naturalism is “imperialistic; it demands ‘full coverage’ . . . and exacts a terribly high ontological price.”[5]

This means that this purer, less-theistically shaped view of naturalism has no place for evil. The Christian philosopher Alvin Plantinga reminds us that the reality of evil—the leading argument used against God’s existence—makes no sense if there is God, no standard of goodness, no way things ought to be:

…could there really be any such thing as horrifying wickedness if naturalism were true? I don’t see how. A naturalistic way of looking at the world, so it seems to me, has no place for genuine moral obligation of any sort; a fortiori [i.e., all the more], then, it has no place for such a category as horrifying wickedness….

[The problem is one of understanding] how, in a naturalistic universe, there could be such a thing as genuine and appalling wickedness. There can be such a thing only if there is a way rational creatures are supposed to live, obliged to live. But naturalism cannot make room for that kind of normativity; that requires a lawgiver, one whose very nature it is to abhor wickedness. Naturalism can perhaps accommodate foolishness and irrationality, acting contrary to what are or what you take to be your own interests; it can’t accommodate appalling wickedness. Accordingly, if you think there really is such a thing as horrifying wickedness (that our sense that there is, is not a mere illusion of some sort), and if you also think that the main options are theism and naturalism, then you have a powerful theistic argument from evil.[6]

Given Plantinga’s point, what would such an argument for God from evil look like? It would look something like this:

If objective moral values exist, then God (most likely) exists.

Evil exists.

Evil is an objective (negative) moral value.

Therefore God (most likely) exists.

So if the (broad) naturalist considers evil a problem that somehow undermines belief in God, this problem turns out to be much more serious for the naturalist. If she believes in real or objective evil, she in fact has two problems to deal with: the problem of evil and the problem of goodness (or the design-plan)—the standard evil presupposes. The theist has ready room for this standard. Again, the problem of evil—the leading anti-theistic argument—turns out to be an argument for God’s existence. After all, if one rejects the reality of God based on the way things ought to be, it is hard to see how anything ought to be the way it is. Without God, there is no design-plan. Things just are.

So as we consider the heartbroken mother, bereft of her dear ten-year-old girl and unable to believe in a God who would allow this, it turns out we are left with even more problems if we remove God from the scene: why think anything evil could exist in the absence of a good God—the source of the design-plan in the first place?

Notes

[1] Susan Neiman, Evil in Modern Thought: An Alternative History of Philosophy (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2002), 246

[2] R. Douglas Geivett, “A Neglected Aspect of the Problem of Evil.” Paper at the Evangelical Philosophical Society meeting, Orlando, FL (November 1998).

[3] C. S. Lewis, Mere Christianity (New York: Macmillan, 1952), 45-46.

[4] From The Fellowship of the Ring, directed by Peter Jackson (New Line Cinema, 2001), based on J. R .R. Tolkien’s work by the same title.

[5] Jaegwon Kim, “Mental Causation and Two Conceptions of Mental Properties.” Paper presented at the American Philosophical Association Eastern Division Meeting (December 1993), 22-23.

[6] Alvin Plantinga, “A Christian Life Partly Lived,” in Philosophers Who Believe, ed. Kelly James Clark (Downers Grove, IL: InterVarsity Press, 1993), 72, 73 (my emphasis).

— Paul Copan is the Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Learn more about Paul and his work at paulcopan.com.

Book Highlight

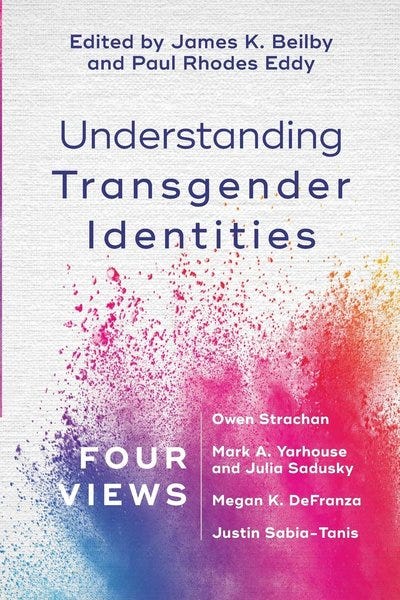

*One of the greatest points of conflict between the Christian worldview and contemporary Western culture is the issue of sexuality—especially homosexuality, and more recently, transgender identity. In order to engage with these issues, it is important to acquaint oneself with the biblical, theological, philosophical, and scientific considerations that play a role in the debate. It’s also very helpful to carefully think through the arguments of those who take non-evangelical views on these matters so that we truly understand what people are saying, and why.

Understanding Transgender Identities: Four Views is a very helpful survey of the major Christian viewpoints, presented by four different proponents of these views, which range from a rejection of transgender as an identity, to a full embrace of it. Each of the four contributors also responds to the others, which provides the benefit of seeing how each position stands up to critique. Finally, the editors have written a substantial introduction that surveys the background, vocabulary, and key psychological and scientific theories that have given rise to the current discussion.

"Every Christian leader needs to think through questions related to transgender identities and experiences. Every Christian leader, therefore, needs to read this book and humbly and critically consider the various views. Paul Eddy and James Beilby have put together a thoughtful team of scholars addressing some of the most important ethical questions facing the church today."

— Preston Sprinkle, president of the Center for Faith, Sexuality, and Gender

James K. Beilby (PhD, Marquette University) is professor of systematic and philosophical theology at Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota. He has written or edited numerous books, including Thinking about Christian Apologetics. Beilby is the coeditor (with Paul Rhodes Eddy) of six successful multiview volumes, including Understanding Spiritual Warfare: Four Views.

Paul Rhodes Eddy (PhD, Marquette University) is professor of biblical and theological studies at Bethel University in St. Paul, Minnesota. He is the author, coauthor, or editor of a number of books, including Across the Spectrum. Eddy is the coeditor (with James K. Beilby) of six successful multiview volumes, including Understanding Spiritual Warfare: Four Views.

Read an extended excerpt from the introduction here.

Find Understanding Transgender Identities: Four Views at Amazon, Baker, and other major booksellers.

* This is a sponsored post.

Book and Resource Deals

Thanks to a number of publishers and ministries, there are currently some highly discounted or free deals on books and other resources.

Fontes Press has 9 Kindle deals, most for $2.99.

Gospel ebooks rounds up a nice collection of sales that will likely end after March 31:

Harvest House Fiction (18 books)

HCCP Fiction (13 books)

Thomas Nelson Non-Fiction (21 books)

Tyndale House Fiction (9 books)

Bethany House Deals (12 books)

Zondervan Monthly Non-Fiction (14 books)

Baker Books Monthly Deals (9 books)

Revell Books Monthly Deals (14 books)

Eerdmans Monthly Non-Fiction (11 books)

David C. Cook E-Books (13 books)

The Preacher's Commentaries (35 books)

Counterpoints Series (36 books)

Gospel Coalition put together this fine list of “Free (or Discounted) Books to Read in Quarantine.”

Logos has some great deals currently on commentaries and other resources, good until the end of March. See here and here.

Fortress Press is running their spring ebook sale. You can see all of the titles here, and find them on Amazon or Barnes & Noble. The deals are good through April 24th. Fortress publishes a number of N. T. Wright’s books.

Crossway is offering a free basic subscription to ESV.org, which includes:

9 study Bibles, including the award-winning ESV Study Bible (containing 20,000+ study notes, 80,000+ cross-references, 200+ charts, 50+ articles, and 240 full-color maps and illustrations)

A suite of original language tools related to The Greek New Testament, Produced at Tyndale House, Cambridge

The complete interactive Knowing the Bible study series which consists of 45 volumes covering the Bible’s 66 books

Streaming Bible audio

Dozens of interactive reading plans and devotionals

Ligonier Ministries just made thousands of lectures, study series, and digital study guides available free for the first time. A number of teaching videos are now available through Amazon Prime Video (you can find them by searching for “Ligonier”).

Photo credit: longhorndave on Visualhunt.com / CC BY

Subscribe

Subscribe to The Worldview Bulletin and receive a master class in worldview training, delivered weekly and monthly directly to your inbox. Receive a year’s worth of equipping for the discounted price of only $3.75 per month!

Wow - can't get more stupid than that? Trump exists - therefore stupidity exists!

hahaha