Greetings, fellow apologists! In this March issue of the Bulletin, Paul Copan continues his series on worldviews and surveys and critiques panentheism and process theology. Paul Gould concludes his two-part series on Christian Platonism, showing that C. S. Lewis held this position. Melissa Cain Travis explains how our planet is fine-tuned for the type of fire needed for modern science to exist, and David Baggett proposes some lessons we can learn from John Wesley on both the importance and limitations of human reason. We also round up some interesting news of note and some great deals on books.

The Truth Is Out There,

Christopher Reese

Editor-in-Chief

Contents

Part One

Questioning Worldviews: Part 6

Panentheism (or Process Theology)

by Paul Copan

The Christian Platonism of C. S. Lewis, Part 2

by Paul M. Gould

Please see the second email for Part Two of the newsletter.

Panentheism (or Process Theology)

By Paul Copan

In this next installment of our brief examination of various worldviews, we look at panentheism or process theology. In this series, we have been noting the greater plausibility and explanatory power of the biblical faith over against these rival worldviews. While many worldviews will point out various truths and important insights, which is what we can expect from God’s general revelation, they still don’t do what Jesus himself does—namely, hold all things together by the power of his word and by his wisdom (Col. 1:17; Heb. 1:3). Jesus gives coherence to reality and brings together the various fragments of truth, goodness, and beauty in other worldviews.

Panentheism: What It Is

God and His Body

While pantheism maintains that everything is God or divine, panentheism treats the relationship between God and the world as analogous to the soul and the body. There is a genuine distinction between God and the world, but a mutual, eternal dependency exists between them. The world is “within” God, and there is a kind of “dance” between God and the world. In classical panentheism, God and the world are necessarily and eternally dependent on each other.

This kind of model of God’s relationship with the world has been adopted by various feminist theologians (e.g., Grace Janzen, Sally McFague), who emphasize God’s loving relationship to the world—as opposed to a kind of commander-commandee relationship. A divine “spirit” is at work, bringing humans into greater harmony with one another and with nature. These feminists reject a traditional God—a “sovereign” who “rules” over creation (monarchical model) because this can lead to oppression of others and destroying the earth’s ecological balance.

Furthermore, process theology (e.g., Alfred North Whitehead) has emphasized two “poles” in God—that God is actually finite but potentially infinite and is constantly realizing “his” potentiality. According to another panentheist, God is continuously active in the open-ended emergent processes of nature.[1]

Creation as Dependence

In the same spirit, the process theologian Alfred North Whitehead rejected the doctrine of creation out of nothing, because it presents God as playing too absolute a role: “He is not before all creation but with all creation.”[2]

Indeed, certain panentheists claiming adherence to the Christian tradition and engaging in the God-science dialogue don’t emphasize the universe’s temporal origination and creation out of nothing. Rather, they use terms such as “immanence” or “ontological dependence.” In fact, Ian Barbour maintained that creation out of nothing—the universe’s absolute origination from God—isn’t a biblical concept. The doctrine of creation is nothing more than the universe’s dependence on God.[1] Barbour believed that we must still “defend theism against alternate philosophies, but we can do so without reference to an absolute beginning.”[3]

Arthur Peacocke, a theologian and philosopher of science, emphasized God’s immanence, and diminished divine transcendence and the significance of the universe’s absolute origination. Instead, God is “continuously creating.”[4] Following in their train, theologian and philosopher Philip Clayton rejects “classical Christian theism” in favor of panentheism. Though he affirms some measure of divine transcendence, nevertheless God and the world are inseparable. Peacocke asserts that whether we may or may not be able to infer or assign a beginning point to the universe (such as with the Big Bang), “the central characteristic core” of creation would remain unaffected—that God is the Sustainer and Preserver of the created order.[5]

Differences Between Panentheism and Traditional Theism

Charting the Differences

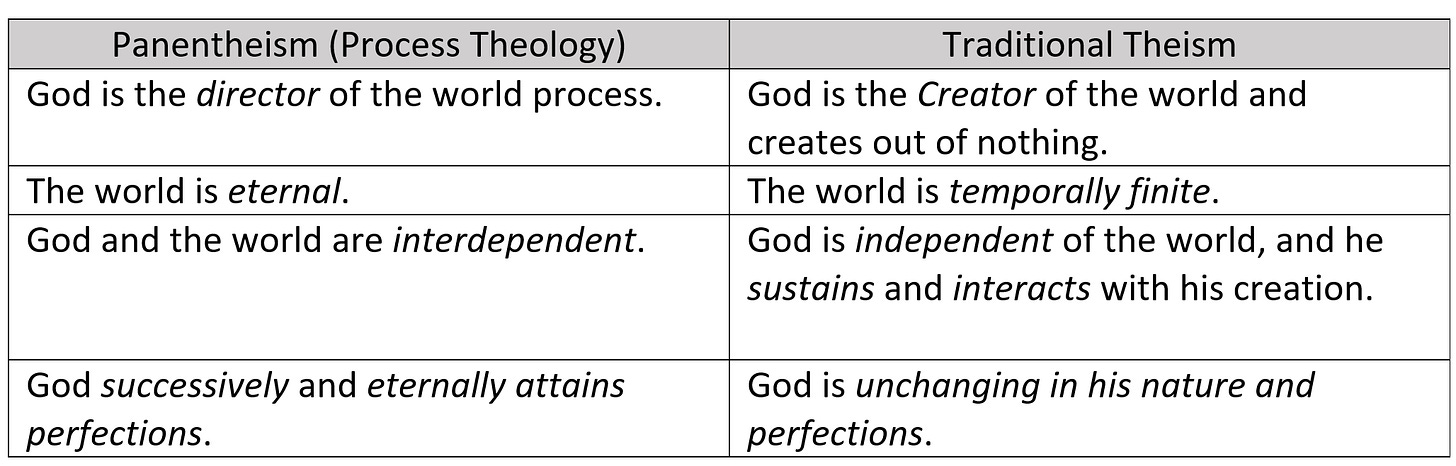

Below is a chart highlighting some of the key differences between panentheism and traditional theism:[6]

Some Biblical and Scientific Considerations

If we examine panentheism or process theology against the backdrop of Scripture and even science, we should take note of the following points.

First, panentheism has failed to take seriously the biblical understanding of the triune God, who is inherently relational and self-giving. Christian theologian Stanley Hauerwas offered this critique of one process theologian’s understanding of God: “One of the things that bothers me about [his] God is that she is just too damned nice!”[7] By diminishing divine transcendence and overemphasizing the immanence of God, process theology’s attempt to salvage divine relationality and intimate engagement with the world becomes an effort in jumping ship far too soon.

For one thing it appears that panentheists/process theologians who have critiqued “classical theism” have treated the traditional understanding of God in a unitarian rather than trinitarian fashion. However, because the Triune God within himself is intrinsically relational and loving, process theism becomes superfluous in attempting to safeguard God’s deeply relating to the world. God is profoundly relational; he interacts with the world; and he is capable of being touched by human actions and even suffering with the world. But this sovereign God who suffers with the world is not incapacitated by it either. Rather, this supremely perfect God guarantees that our own perfection will be reached in the new heavens and new earth when Christ returns. Panentheism cannot guarantee such an outcome.

Second, pantheism goes against the findings of science, which point to the beginning of the universe. This picture of the world looks very much like Genesis 1:1—creation out of nothing. That is, although God has eternally existed, the finite universe has not. It is dissipating and winding down, suggesting it has been wound up. So God does not eternally coexist with the world as his “body.”

Third, if what we mean by God is the “greatest conceivable being” or the maximally great being, then process theism presents us with a diminished deity. God’s power is diminished by the fact that God needs the world coexisting with him. God’s transcendence is diminished by God’s immanence. Also, God has no genuine freedom to create out of nothing if he wanted to. All God can do is direct the world, but he has no freedom to bring into existence a world independent of himself.

While the Scriptures affirm both divine transcendence and immanence (Acts 17:28: “In Him we live and move and have our being”), panentheism sacrifices transcendence and other great-making qualities of God that leave us with an inferior version of deity that cannot guarantee that all things will ultimately be put to rights in the end.

Notes

[1] Arthur Peacocke, Creation and the World of Science, 1978 Bampton Lectures (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1979), 353.

[2] Whitehead, Process and Reality (New York: Free Press, 1978), 343.

[3] Ian Barbour, “Religious Responses to the Big Bang,” in Cosmic Beginnings and Human Ends: Where Science and Religion Meet, ed. Clifford N. Matthews and Roy Abraham Varghese (Chicago: Open Court, 1995), 396.

[4] Arthur Peacocke, God and Science: A Quest for Christian Credibility (London: SCM Press, 1996), 13.

[5] Peacocke, Creation and the World of Science, 79.

[6] Taken from Norman Geisler, Christian Apologetics (Grand Rapids: Baker, 1976).

[7] Stanley Hauerwas, Wilderness Wanderings: Probing Twentieth-Century Theology and Philosophy (repr., New York: Routledge, 2018), 29.

— Paul Copan is the Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics at Palm Beach Atlantic University. Learn more about Paul and his work at paulcopan.com.

Image by Evgeni Tcherkasski from Pixabay

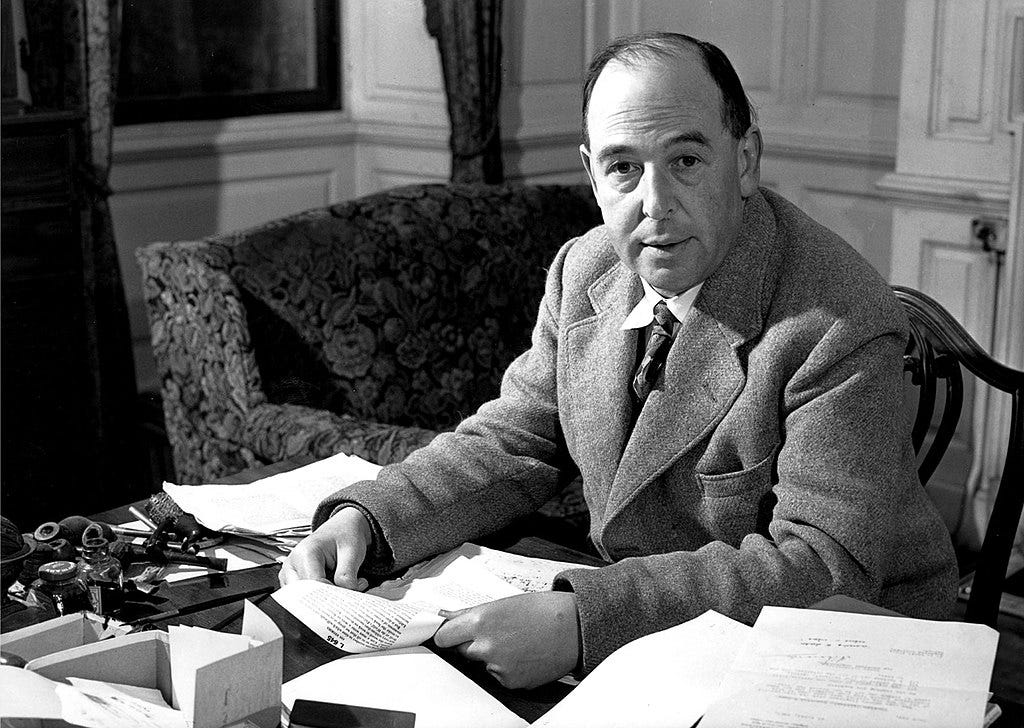

The Christian Platonism of C. S. Lewis, Part 2

By Paul M. Gould

In last month’s Worldview Bulletin essay, I unpacked the Christian Platonic vision of reality. In this month’s essay, I’ll (briefly) argue that C. S. Lewis was a Christian Platonist.

To begin, Lewis wanted to be identified as a Christian Platonist. One particularly poignant example of this is found in the closing sections of The Last Battle. The forces of good and evil come to a head, and Aslan ushers in the end of Narnia and the beginning of eternity. Toward the end of the book, the old Narnia has ended and the faithful have entered through a magical door into Aslan’s country. As they explore this new world, they notice that it looks a lot like the old Narnia, just better—richer, purer, more real, untainted by evil, eternal. And Lord Digory, who had been present during the creation of Narnia (another wonderful tale found in The Magician’s Nephew), blurts out:

It’s all in Plato, all in Plato: bless me, what do they teach them at these schools!

What we find here, and in many places, is Lewis using Platonic concepts to explain a deep truth of the Christian faith. In this instance, we learn that when this age has passed, and God redeems and restores all of creation, the faithful will finally experience life the way it is supposed to be. In a sense, our experience will seem more real, because it will be untainted by sin and misery and suffering. As Lewis puts it in The Great Divorce, “Heaven is reality itself. All that is fully real is Heavenly. For all that can be shaken will be shaken and only the unshakeable remains.”[1]

In eternity, the faithful will experience intimacy with God and harmony with each other as we worship, serve, and explore for eternity the new heavens and new earth (Revelation 21:1). We shall be in Aslan’s country and the “shadow lands” (another Platonic reference common in Lewis) will be no more. Lewis wished to be understood as a Christian Platonist.

Next, let’s consider one of my favorite passages from Lewis’s essay “The Weight of Glory.” Lewis writes:

The books or the music in which we thought the beauty was located betray us if we trust in them; it was not in them, it only came through them, and what came through them was longing. These things—the beauty, the memory of our own past—are good images of what we really desire; but . . . they are not the thing itself; they are only the scent of a flower we have not found, the echo of a tune we have not heard, news from a country we have never yet visited.

Let me make four observations about this quote:

First, notice the connection between art (stories and music), beauty, and longing. Lewis understood, like Plato, that “beauty evokes desires” (as the theologian David Bentley Hart states it in his book The Beauty of the Infinite) and thus he, like the poets and storytellers of old, writes what he calls later in his essay “such lovely falsehoods” as the Narnia tale. Lewis dubbed this intense longing (most often experienced through engagement with beauty) “romance”—and thus he intentionally employed what he called “romantic imagination” in his art and literature to evoke and awaken desire.

Second, note the participatory nature of reality on full display: we have beautiful things (books and music) and we have the experience of Beauty itself.

Third, note that this participatory ontology undergirds a distinct (and Christian Platonic) way of seeing called by the medievals “continuation” or “co-seeing.” The idea of continuation according to the theologian Junius Johnson “is to see two things with one simple act of seeing.”[2] In acts of co-seeing, one thing is seen through the other. Thus, continuation is a kind of spiritual vision that enables us to see the second object (in this case Beauty itself) within the first object (in this case beautiful things). I love how Harvard professor Elaine Scarry describes our encounter with beautiful things in this world in her book On Beauty and Being Just as “small wake-up calls to perception” that “[spur] lapsed alertness back to its most acute level.”[3] More broadly, given the fact that every created thing points to and illuminates the divine, everything, for those of us who have eyes to see (as Lewis encourages us) points to and illuminates the divine.

Finally, the means of acquiring truth is deeply Platonic. One is admitted to important knowledge of reality because of a love and reverence for the new truth glimpsed. As Lewis puts it in Out of the Silent Planet (part of his Ransom Trilogy), when speaking of the hero Ransom’s experience of the eldila: “Through his knowledge of the creatures and his love for them he began, ever so little, to hear [their music] with their ears.”[4]

What we love, as seekers of truth, goodness, and beauty, shapes what we see and hear [for more on this concept, see David Baggett’s recent series on Lewis’s novel Till We Have Faces (part 1, 2, 3, and 4)]. Further, in order to gain wisdom, we must turn our souls in the right direction. We must turn toward “the good” as Plato would put it (in his discussion in Book 7 of the Republic and the Allegory of the Cave). We must turn away from the “stream of experience” as Lewis puts it in The Screwtape Letters. Or as the writer of the book of Hebrews puts it, we must “fix our eyes on Jesus, the author and perfecter of our faith” (Hebrews 12:2).

Notes

[1] C. S. Lewis, The Great Divorce (San Francisco: HarperSanFrancisco, 2001), 70-71.

[2] Junius Johnson, The Father of Lights: A Theology of Beauty (Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2020), 56.

[3] Elaine Scarry, On Beauty and Being Just (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1999), 81.

[4] C. S. Lewis, Out of the Silent Planet (New York, NY: Scribner, 2003), 130.

— Paul M. Gould is an Associate Professor of Philosophy of Religion and Director of the M.A. Philosophy of Religion program at Palm Beach Atlantic University. He is the author or editor of ten scholarly and popular-level books including Cultural Apologetics, Philosophy: A Christian Introduction and The Story of the Cosmos. He has been a visiting scholar at Trinity Evangelical Divinity School’s Henry Center, working on the intersection of science and faith, and is the founder and president of the Two Tasks Institute. You can find out more about Dr. Gould and his work at Paul Gould.com and the Two Tasks Institute. He is married to Ethel and has four children.