Natural Law: An Introduction, Part 2

By Nicholas K. Meriwether

Universal law is the law of Nature. For there really is, as everyone to some extent divines, a natural justice and injustice that is binding on all men, even on those who have no association or covenant with each other.

Aristotle, Rhetoric, Bk. I, 13

In part 1, we said that a theory of a given human activity can be distinguished at three levels: Level 1 is practical, Level 2 is in relation to society, culture, and history, and Level 3 is in relation to ultimate reality, which is the realm so to speak of philosophy and religion. We also looked at what is needed for an ethical theory. An ethical theory should provide:

(1) Level 1 (practical) principles as to what we should do, including precepts, rules, duties and obligations, but very importantly, what we are forbidden to do.

(2) How we become capable of performing our duties, and also capable of avoiding bad, wrong, or evil actions.

(3) What the purpose or goal of moral actions is in terms of human flourishing and our own individual flourishing, but also in relation to God’s nature and purposes.

(4) On what basis we know right from wrong, and good from evil. This is both in relation to Level 3 questions of what the nature of morality is, but also how we know in a given situation what we should do, which occurs at Level 1.

One reason we start with the theoretical nature of ethics is the perennial danger that Level 1 and 2 considerations, the levels that look at things from a practical standpoint and the standpoint of history, society, and culture, will dominate our attitude toward and beliefs about ethics. There is of course nothing wrong with asking how history and culture affect our views of morality, but asking these questions while ignoring Level 3 will tend to undermine our confidence that ethics has to do with something that is real and true. Let’s look at an influential current example.

Probably most of you have heard the phrase “social construct.” No doubt, you’ve heard the claim that gender (whether a person is male or female), our attitudes about the family, male and female roles, or class is a “social construct.” So what is a social construct? Here’s a concise definition:

A social construct is a concept that exists not in objective reality, but as a result of human interaction. It exists because humans agree that it exists.

A good example of a social construct is etiquette. It’s considered extremely rude in Western culture to burp out loud during a meal. But in certain cultures, it’s considered a compliment because it indicates that the food is satisfying. Thus, whether burping is good or bad manners doesn’t seem to reflect objective reality, but one’s culture, that is, whether the people of the culture “agree” that it’s rude. We can say similar things about other rules of etiquette, such as how tableware is placed, or the style of clothing that a person should wear on various occasions, say, weddings vs. funerals. These seem to have been established by social agreement rather than the ultimate nature of reality.

Frequently added to the view that an ethical norm is a social construct is that it’s socially constructed to give some people power over others, such as, for example, that it’s morally appropriate to give nobles rights that serfs don’t have. But notice it’s very tempting to slip from the belief that some behavioral rules are social constructs to the idea that all behavioral rules are social constructs, although this doesn’t follow logically at all.

Against social constructivism, some philosophers seek to defend objectivity in ethics, that there really are enduring ethical norms not based merely on human agreement, and that they are knowable. A term for this view is ethical realism. To counter social constructivism, they use various arguments designed to show that constructivist views, if taken at face value, issue in absurdity or have very harmful consequences. For instance, if someone claims that a given moral belief is just a social construct designed to give some people power, why can’t we say that his view of ethics is just a social construct designed to give him power? If the person responds that he is showing that the exercise of power for its own sake is wrong, we can respond by asking why this view isn’t a social construct, too? A steady diet of social constructivism will undermine all moral beliefs, not just the ones that the constructivist wants us to abandon, but even his view that the exercise of power for its own sake is wrong.

Now, there’s nothing at all wrong with pointing out logical inconsistencies. But notice: Just pointing out that someone’s wrong isn’t yet a theory of ethics. Much more needs to be said. This is where natural law comes in, especially, because it provides an account of what moral truth is, and how we know it.

Defining Natural Law

So what exactly is natural law? The shortest, quickest, and easiest explanation is as follows:

I. The content of the Ten Commandments. This includes both the “first table,” Commands 1-4, that we should worship and obey God, and the “second table,” Commands 5-10, that we should love our neighbor as ourselves. More specifically, loving one’s neighbor includes that we should honor those in authority (Fifth Commandment), and also not murder (Sixth), nor commit adultery (Seventh), steal (Eighth), lie (Ninth), or covet (Tenth). (We’ll explicate these later.) On natural law theory, these don’t have exceptions, though there may be some disagreement in application, which is what keeps theologians and philosophers busy.

II. The purpose and design of nature as we observe it. This means that for any observed aspect of human nature, if we are designed to do (x), we should do it, and not do the opposite, with certain exceptions. (As before, the exceptions are what keep theologians and philosophers busy.) The simplest and most straightforward reason for this is that God designed nature for our benefit. So acting in accordance with our fundamental design is good and proper, and violating it is bad and improper.

An example of the design and purpose of human nature is that we have minds. In fact, we have extremely powerful minds, minds that can abstract, analyze, synthesize, infer, and consider Levels 1-3 thoroughly and carefully in respect to just about anything. So we should cultivate and train our minds, not abuse them through drugs or habitual forms of entertainment that deaden them. Now, under special circumstances, a person may have to neglect the cultivation of his mind for a higher purpose, such as rearing very small children—also part of the design and purpose of human nature. But otherwise, “a mind is a terrible thing to waste,” as the old UNCF ads used to say.

Natural Law, Scripture, or Both?

But if Scripture gives us the Ten Commandments, why do we need the natural order? And by the same token, If we have the natural order, why do we need the Ten Commandments?

Perhaps the most famous expositor of natural law, at least in Christian theology, is Thomas Aquinas. The term he uses for Scripture, especially the ethical commands of Scripture, is “divine law.” He wrestles specifically with this question as to why we would need both divine law and natural law. Part of his answer is that it’s easy for people to become uncertain of natural law without God’s affirmation through Scripture. And of course, we see this all around us today. Our culture slipped away some time ago from the dictates of natural law, even though they’re fairly obvious, and have replaced them with radical individual autonomy and so-called “authenticity,” which often means simply freedom from any kind of moral, social, or natural restraint. Once we divorced Scripture’s imprimatur from natural law, it became first debatable, then questionable, then irrelevant, and now more recently and perhaps predictably, offensive. What many failed to see is that the first four commandments—that we should worship God alone, not create idols, revere his name, and set aside time each week for formal worship and fellowship—are critical to the acquisition of wisdom, which is the ability to know “every good path,” that is, to act with righteousness and justice, and to avoid evil. This connection is summarized beautifully in Proverbs 2:1-15.

But if we have Scripture, why do we need to observe and learn from the natural order? In fact, Scripture assumes we already know natural law. Classic examples can be found in Prov. 6:6, in which we’re encouraged to observe the ant in order to learn to be industrious, or the many passages in which nations without Scripture are judged for violating God’s design, such as Lev. 20:23 or Amos 1. In the New Testament, Paul explicitly states that the moral law is written on the human conscience (Rom. 2:15). Moreover, Scripture assumes we can’t interpret it without knowing natural law. An example is the definition of male and female, which has become incredibly controversial of late. While we know from Scripture that God created us “male and female” (Gen. 1:27), nowhere does it say how to define these. Do we define these in relation to whether we are naturally designed to menstruate or bear children? Or the presence or absence of the Y chromosome? Scripture doesn’t say, rather it just assumes we can tell the difference. The fact that the definition is even controversial says more about us than about the clarity of Scripture on this question, fulfilling the warning of Rom. 1:28.

So the short answer to the question, What is the relationship of natural law to Scripture? is that they’re mutually supportive. Both are necessary to moral understanding, and together they are the foundation for it.

— Nicholas K. Meriwether is Professor of Philosophy at Shawnee State University in Portsmouth, OH. He has taught the Ethics requirement at SSU for 26 years. He received an MA in Christian Thought from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and a PhD in Philosophy from Purdue University. He has published in the areas of moral psychology, Critical Theory, Islamic militancy, and the role of ethics instruction in higher education. He and his wife, Janet, have three grown children. They are members of the Presbyterian Church in America.

Image by David Mark from Pixabay

[Sponsored]

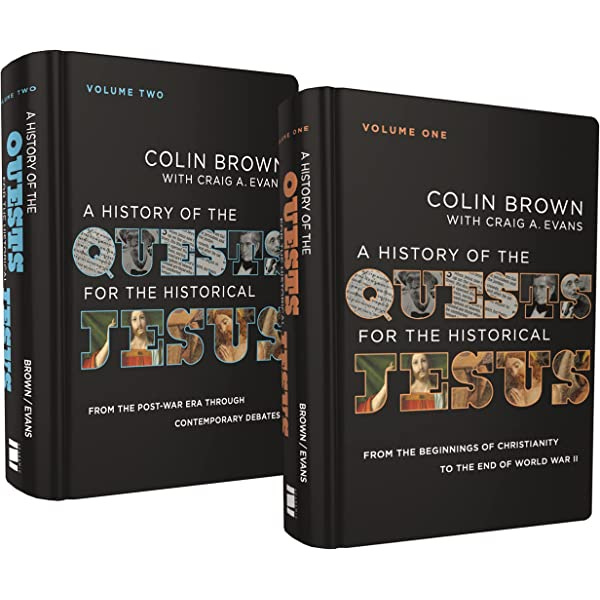

A History of the Quests for the Historical Jesus (2 Vols.)

Jesus' life and teaching is important to every question we ask about what we believe and why we believe it. And yet there has never been common agreement about his identity, intentions, or teachings—even among first-century historians and scholars. Throughout history, different religious and philosophical traditions have attempted to claim Jesus and paint him in the cultural narratives of their heritage, creating a labyrinth of conflicting ideas.

From the evolution of orthodoxy and quests before Albert Schweitzer's famous “Old Quest,” to today's ongoing questions about criteria, methods, and sources, A History of the Quests for the Historical Jesus not only chronicles the developments but lays the groundwork for the way forward.

The late Colin Brown brings his scholarly prowess in both theology and biblical studies to bear on the subject, assessing not only the historical and exegetical nuts and bolts of the debate about Jesus of Nazareth but also its philosophical, sociological, and theological underpinnings. Instead of seeking a bedrock of “facts,” Brown stresses the role of hermeneutics in formulating questions and seeking answers.

Colin Brown was almost finished with the manuscript at the time of his passing in 2019. Brought to its final form by Craig A. Evans, this book promises to become the definitive history and assessment of the quests for the historical Jesus.

Volume One covers the period from the beginnings of Christianity to the end of World War II.

Volume Two covers the period from the post-War era through contemporary debates.

“Not since the grand survey of Albert Schweitzer at the beginning of the twentieth century have we seen—especially in English—such a vast review of academic (and at times popular) literature on the historical Jesus.”

—John P. Meier, University of Notre Dame

“In this comprehensive two-volume study, the late Colin Brown brings together the rich fruits of his lifelong studies on Jesus in Christian theology. . . . For future Jesus research, this thorough study is an indispensable tool.”

—Jens Schröter, Humboldt University

See our Worldview Bulletin excerpt from Volume 1 here.

Find A History of the Quests for the Historical Jesus at Amazon, Zondervan, and other major booksellers. Volumes 1 and 2 are also sold individually in print and Kindle versions.

Join us on Saturday, February 25th, when Bulletin team member Dr. Melissa Cain Travis will present a tutorial on the topic of the theistic implications of the comprehensibility of the cosmos.

The meeting, open to any paid Bulletin subscriber, will take place by Zoom from 3pm-4pm Central. We’ll be sending a reservation form to all paid subscribers in early February, and have room for 20 attendees. Following a presentation by Dr. Travis, we’ll open the floor and have an interactive, conversational discussion on this topic. Each attendee will receive a discussion guide. To allow for an open, interactive discussion, we’re limiting the attendance to 20, and will take reservations on a first-come, first-served basis. If you’re not currently a subscriber, just click the button below, where you’ll receive our holidays discount and best subscription offer of the year.

In Dr. Travis’s words, “For more than two millennia, great thinkers of the Western Tradition have marveled over the rational order of the cosmos and humankind's ability to discern it. Johannes Kepler, a giant of the scientific revolution, understood the powerful theistic implications of the mathematics-nature-mind resonance that makes the natural sciences possible.”

Dr. Travis will be sharing these insights from her new book, Thinking God's Thoughts: The Miracle of Cosmic Comprehensibility.

Advertise in The Worldview Bulletin

Do you have a book, course, conference, or product you’d like to promote to 5,770 Worldview Bulletin readers? Click here to learn how. We’re currently booking for February-March.

Support The Worldview Bulletin

Your support makes The Worldview Bulletin possible! We couldn’t do this without the support of you, our readers. We would be grateful for your help in any of the following ways:

Give a gift subscription to a family member or friend who would benefit, or subscribe a group of four or more and save 25%.

Make a one-time or recurring donation.

Become a Patron and receive signed books from our team members.

“The Worldview Bulletin is a wonderful resource for the church. It’s timely and helpful.” — Sean McDowell, associate professor in the Christian Apologetics program at Talbot School of Theology and author of The Fate of the Apostles: Examining the Martyrdom Accounts of the Closest Followers of Jesus (Routledge)

“Are you looking for a way to defend your Christian worldview? If so, look no further. At The Worldview Bulletin you’ll encounter world-leading scholars dispensing truth in a digestible format. Don’t miss out on this unique opportunity to engage in this meeting of the minds.”

— Bobby Conway, Founder of The One-Minute Apologist, author of Does God Exist?: And 51 Other Compelling Questions About God and the Bible (Harvest House)

“I find The Worldview Bulletin very stimulating and would encourage all thinking Christians to read it.”

— John Lennox, emeritus professor of mathematics, University of Oxford, emeritus fellow in mathematics and philosophy of science, Green Templeton College, author of Cosmic Chemistry: Do God and Science Mix? (Lion)

“The Worldview Bulletin shines a brilliant light of truth in a darkening world. These authors, who are experts in their field, consistently provide logical, rational, moral and most importantly biblical answers, in response to the deceitful narratives we are bombarded with daily. I have found it a great source of enlightenment, comfort, and inspiration.”

— B. Shadbolt, Subscriber, New South Wales, Australia

“The Worldview Bulletin is a must-have resource for everyone who’s committed to spreading and defending the faith. It’s timely, always relevant, frequently eye-opening, and it never fails to encourage, inspire, and equip.”

— Lee Strobel, New York Times bestselling author of more than forty books and founding director of the Lee Strobel Center for Evangelism and Applied Apologetics

“The Worldview Bulletin is a wonderful resource for those desiring to inform themselves in matters of Christian apologetics. Learn key points in succinct articles written by leading scholars and ministers. All for the monthly price of a cup of coffee!”

— Michael Licona, associate professor of theology at Houston Christian University and author of Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? What We Can Learn From Ancient Biography (Oxford University Press)