So I said that in this installment I would begin to discuss my dissertation. Writing a dissertation is a daunting task. For many, it’s the first real test of whether or not one can rise to the occasion in graduate school and produce something of an original work in one’s field. The prospect of failing seems to hang heavily in the air. I remember perusing the finished, bound dissertations from previous students in my program in the department’s library and reminding myself it could be done. I prayed a lot during that time that God would help me write something solid.

I filled up the binder I mentioned last time with dozens and dozens of relevant articles on the Euthyphro Dilemma. Then I filled up another, then another—I ended up with about a dozen or so binders full of articles. Then I set myself to the task of reading each one and taking notes on them. My plan for quite a while was to read one article per day and write up a summary about it, and I kept to that plan for many consecutive months. It doesn’t sound like a lot, and perhaps it wasn’t, but there’s quite a bit of power to doing anything consistently.

As I look back at that part of my life and work, I realize in retrospect that my approach could have been better. What I took to be a measure of hostility toward my theistic approach was probably exacerbated by my being a bit overly punchy at times. Christians in secular environments do sometimes find themselves feeling under attack, but on occasion they can imagine there’s more opposition than there really is. And without enough humility, they can exacerbate tensions needlessly.

I suspect I made numerous mistake during that time. I could be overly argumentative. I could fail to listen to and learn from opposing views as much as I should have. While at times I could be riddled with self-doubts, at other times I could be arrogant, thinking I had things figured out that I didn’t. I could underestimate the difficulties attending my own positions and exaggerate the challenges faced by my interlocutors. Admittedly I felt put on the defensive at times, and figured at the time that my attitude and approach was appropriate and called for, and sometimes it was. But sometimes it wasn’t. I was young and ambitious and, in some ways, emotionally immature. I could and should have been more cooperative and more teachable, but I think too often I saw the challenge of defending theistic ethics as my part to play in the culture war.

As the years have gone by, the culture war mentality has grown tired for me. Certainly we are involved in a battle of sorts. The Bible tells us as much, but it’s a battle of a certain kind. We wrestle, we are told, not against flesh and blood, but against principalities and powers, spiritual forces of darkness, and the like. This surely means that we ought to bathe our projects, whether it be a doctoral dissertation or anything else, in a great deal of prayer. We need to pray for God to inspire our work and empower us to do his will. But our enemies are not fellow human beings made in God’s image. In retrospect, I can see that I had a great deal more to learn from my secular teachers than to teach them. They were superb philosophers. I could have disagreed with them on occasion with quite a bit more grace and understanding.

It’s taken me a while to learn this lesson and apply it more broadly. In my reading during much of graduate school, I was often too fixated on points of disagreement with those I read. I was always poised to look for mistakes, for leaps of reasoning, for nefarious implicit assumptions. That can and should be part of how we read critically, and I got it down to a science. But where I lagged behind was reading charitably, looking for genuine insights even among those I differed from, finding common ground, even shared humanity.

If I were to be honest, I think at root I was motivated all too often by a sort of fear. Fear that if I conceded too much, my own approach would fall short. Fear of not being countercultural enough. Fear of allowing myself to be overly affected by a secular mindset. I was still trying to spread my intellectual wings and find my voice, and it was intimidating to be surrounded by lots of good thinkers who disagreed with me and didn’t share my worldview convictions. The temptation to hunker down and go into a survival and combative mode was a strong one. But in time I came to see that if we work hard and master our field, we can be confident without being dogmatic. We can have something to teach while remaining teachable, be tenacious without being defensive. We can have the courage of our convictions while being appropriately modest.

At any rate, the dissertation gradually took shape. I wanted to hold off giving individual chapters to my advisor until I wrote the whole thing in order to articulate my vision of how it all held together without getting derailed along the way. This may have led to the dissertation taking longer than it otherwise would have, but the experience did give me the chance to spell out my vision at the time, such as it was, of theistic ethics. Again, the dissertation was an attempt to defend theistic ethics from various objections often thought intractable, many of them deriving from the Euthyphro Dilemma.

The dissertation ended up five chapters long. I started by laying out the Euthyphro Dilemma, then I discussed an Anselmian conception of God (omnipotent, omnibenevolent, etc.), then a theory of the good, then a theory of the right, then a chapter called “Why a Good God Issues Bad Commands.” I’ll discuss aspects of each chapter next time, but two last things for now. I’m looking at my dissertation as I write this, and I note two things. It’s dedicated to my parents: “To my parents, Leonard and Evelyn Baggett, for their years of support and encouragement, whose lives provided to me a model of practical theistic ethics.” And of the four committee members, two of them have, like my parents, now passed away: Bill Stine and Herb Granger. Such fond memories of them all. A poignant reminder we’re here but for a season.

— David Baggett is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Center for the Foundations of Ethics at Houston Christian University. He is the author or editor of about fifteen books, most recently Ted Lasso and Philosophy: No Question Is Into Touch edited with Marybeth Baggett.

[In partnership with our sponsors]

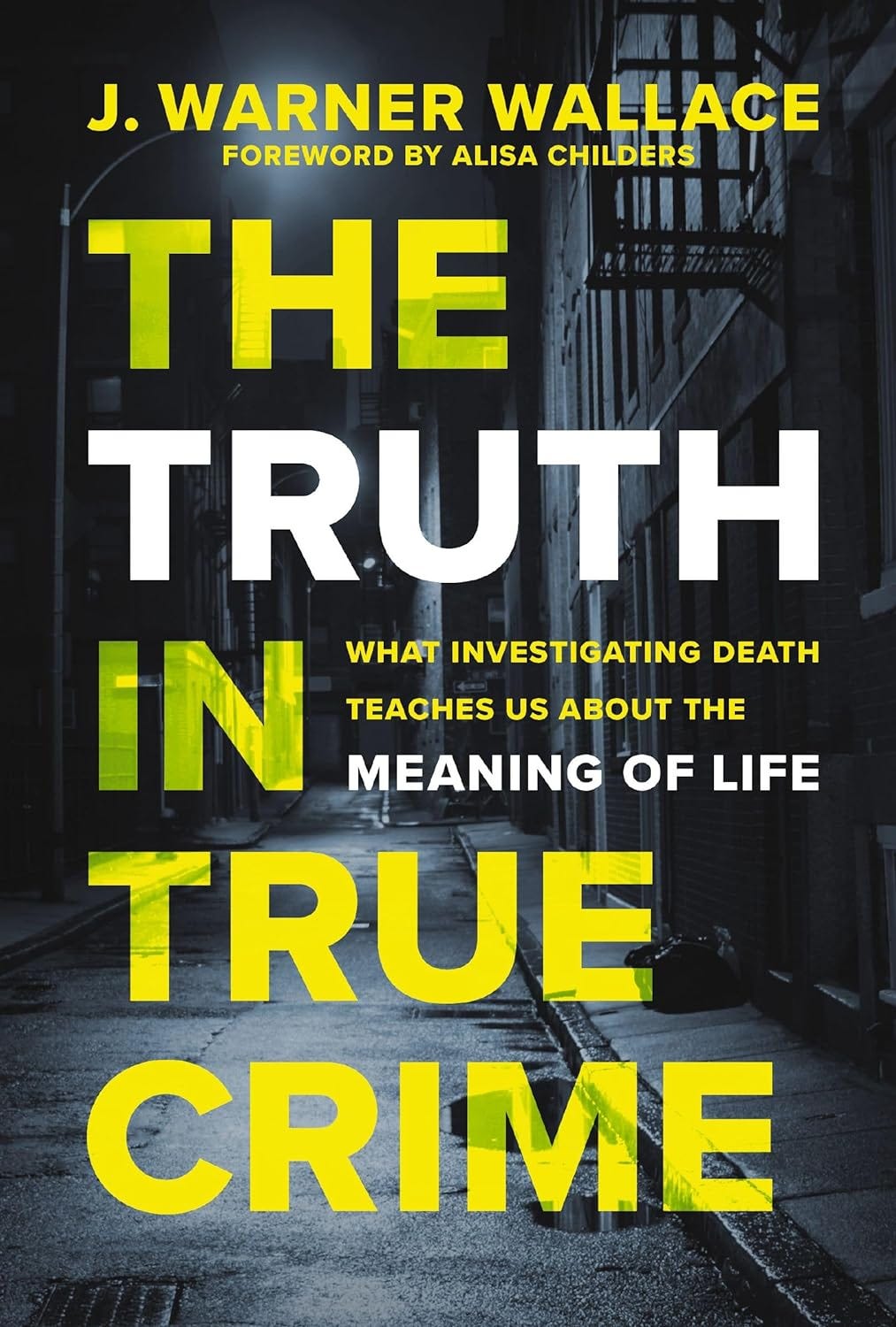

The Truth in True Crime

What Investigating Death Teaches Us About the Meaning of Life

For decades, cold-case homicide detective J. Warner Wallace investigated the causes behind deaths and murders, chasing one lead after another as he attempted to solve the case. Several of these cases remain open, unsolved mysteries. . .

But even those that haven't yet revealed the identity of the killer do expose the truths of human nature: what's important to us, what threatens our well-being, and what causes us to flourish.

Join Wallace as he investigates life lessons he learned as a detective, so that you can:

Better understand your own identity and the identity of your Creator.

Rethink the nature of death so you can live a better life.

Uncover life-truths gleaned from both contemporary murder investigations and ancient biblical wisdom.

Discover profound attributes of human beings that will guide you down the path of true self-discovery.

Each chapter introduces you to an investigation of a death as Wallace and his partner Rick chase down leads and along the way learn guiding principles to help you thrive and flourish as a human being created in the image of God.

“In The Truth in True Crime, J. Warner Wallace shares 15 critical insights about human flourishing that he learned from years of chasing criminals and convicting killers. He found out that what many learn the hard way stumbling through life might have been learned the easy way heeding the ancient insight in Scripture. Wallace's latest work is a storehouse of wisdom, both life wisdom and biblical wisdom—which turn out to be the same thing. You will be the wiser for feasting on it.”

— Gregory Koukl, President of Stand to Reason, author of Street Smarts, Tactics, and The Story of Reality.

See our recent excerpt from The Truth in True Crime here.

Find The Truth in True Crime at Zondervan, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Christianbook.com, and other booksellers.

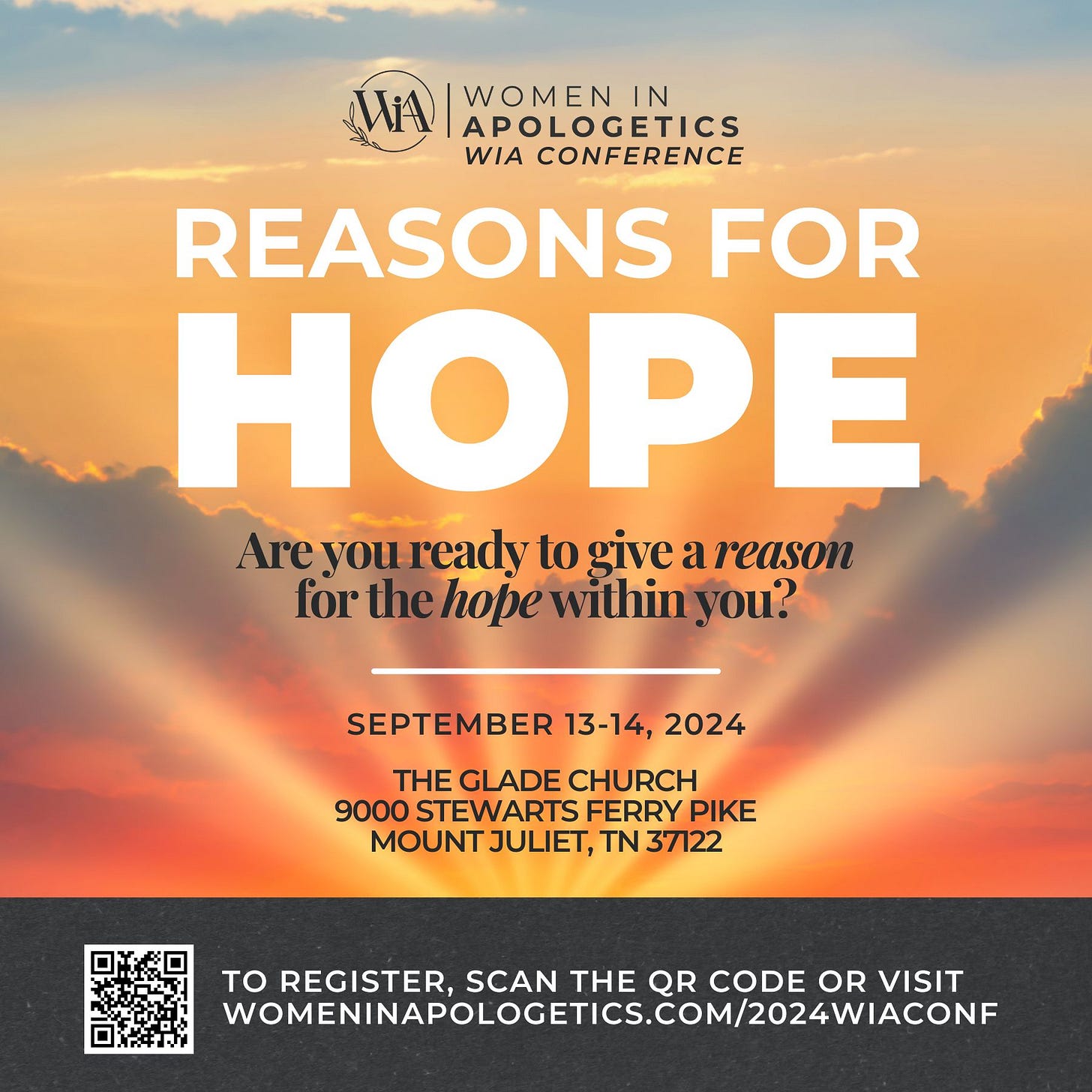

Learn more and register here: https://womeninapologetics.com/2024wiaconf.

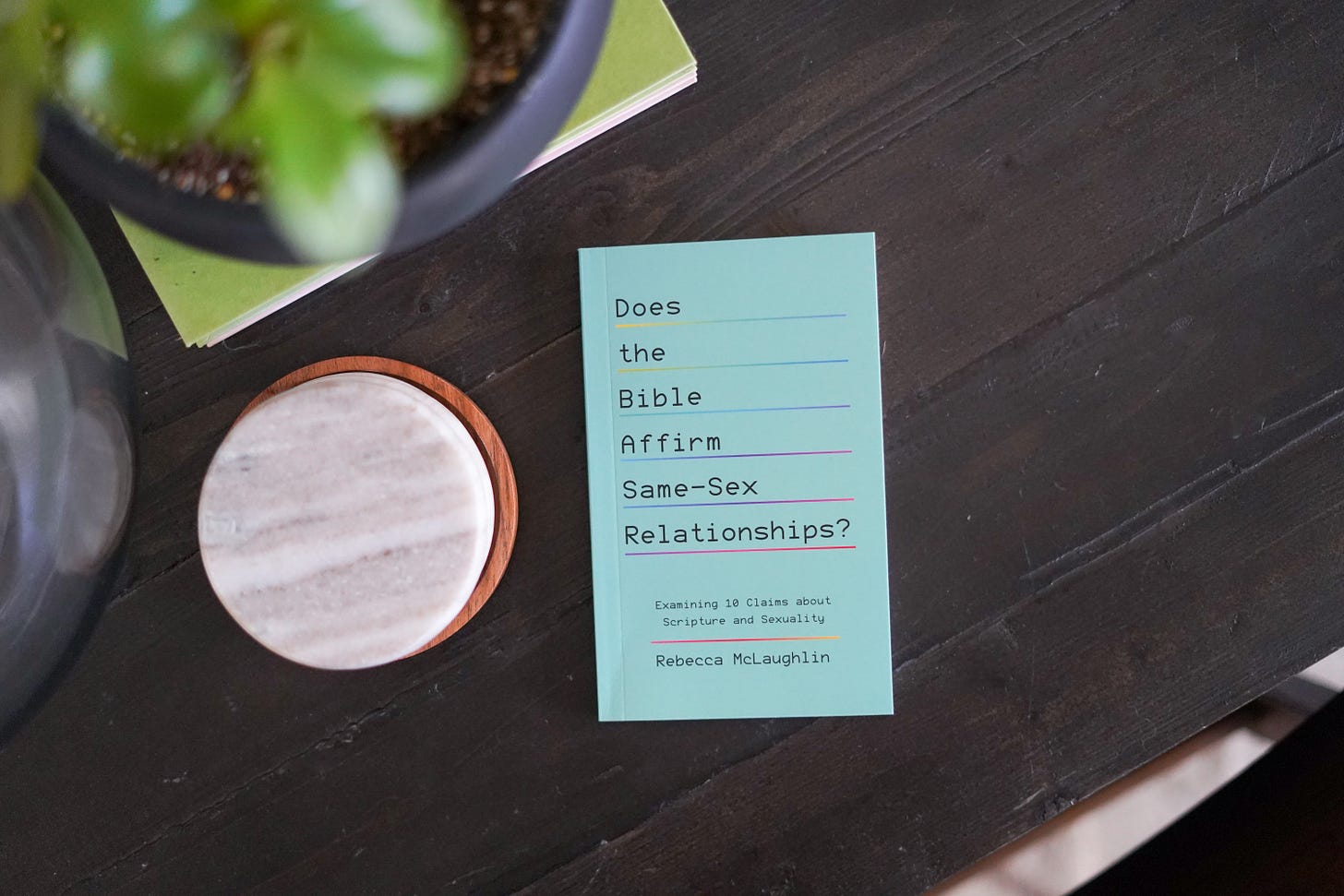

Does the Bible Affirm Same-Sex Relationships?

Examining 10 Claims about Scripture and Sexuality

In this concise book, Rebecca McLaughlin looks at ten of the most common arguments used to claim that the Bible affirms same-sex sexual relationships. She analyzes the arguments and associated Bible passages one by one to uncover what the Bible really says.

For Rebecca, as someone with a lifelong history of same-sex attraction, this is not just an academic question. But rather than concluding that the Bible does affirm same-sex marriage, she points readers to the gospel purpose of male-female marriage, a different kind of gospel-centered love between believers of the same sex, and God's life-and-love-filled vision for singleness.

“It can be easy for Christians today to wonder if we’ve got it wrong on an issue as high-stakes as same-sex sexuality. Deeply biblical, and illustrated in real-life examples, Rebecca McLaughlin’s book shows us the Bible’s consistent and compelling vision for human sexuality. Christians will find this illuminating, reassuring, and deeply encouraging.”

— Sam Allberry, Pastor at Immanuel Church, Nashville; author of Is God Anti-Gay? and What Does God Have to Say About Our Bodies?

See our recent excerpt from Does the Bible Affirm Same-Sex Relationships? here.

Find Does the Bible Affirm Same-Sex Relationships? at The Good Book Company and other booksellers.

Advertise in The Worldview Bulletin

Do you have a ministry, book, course, conference, or product you’d like to promote to 7,543 Worldview Bulletin readers? Click here to learn how. We’re currently booking for August-September.

Subscribe to The Worldview Bulletin

The Worldview Bulletin thrives when readers subscribe. Sign up here to access all of our resources and support our work of commending and defending the Christian worldview. You can also give a one-time donation here at our secure giving site.

“The Worldview Bulletin is a must-have resource for everyone who’s committed to spreading and defending the faith. It’s timely, always relevant, frequently eye-opening, and it never fails to encourage, inspire, and equip.”

— Lee Strobel, New York Times bestselling author of more than forty books and founding director of the Lee Strobel Center for Evangelism and Applied Apologetics

“Staffed by a very respected and biblically faithful group of Evangelical scholars, The Worldview Bulletin provides all of us with timely, relevant, and Christian-worldview analysis of, and response to, the tough issues of our day. I love these folks and thank God for their work in this effort.”

— JP Moreland, distinguished professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology (Crossway)