Complex relationships are often best envisaged using metaphors, which are now recognized as more than rhetorical embellishments to make our language more interesting and are rather seen as powerful cognitive tools for our conceptualization of the world. Such metaphors are helpful in the imaginative representations of disciplinary boundaries, the mapping of complex structures, and the framing of potential relationships. The most influential metaphor used to conceptualize the relation of Christianity and the natural sciences is that of their intrinsic and necessary “conflict” or “warfare.” Though long discredited by historical scholarship, the metaphor retains an appeal that ensures its constant and uncritical repetition in the popular media.

Yet there are alternative metaphors within the Western intellectual tradition in which the potential for productive and meaningful conversations between Christian theology and the natural sciences is acknowledged and actualized. The most important of these is the “two books” metaphor, which emerged during the early medieval period (though it can be traced back to the patristic age) and was further developed during the Renaissance. This metaphor invites us to see God as the author or creator of two distinct yet related “books”—the natural world and the Bible—and thus to imagine nature as a readable text that requires interpretation, in a manner comparable to the Christian interpretation of the Bible.

One of the clearest statements of this approach is found in the writings of Sir Thomas Browne (1605–82), particularly his idiosyncratic work Religio Medici (1643): “There are two Books from whence I collect my Divinity; besides that written one of God, another of His servant Nature, that universal and publick Manuscript, that lies expans’d unto the Eyes of all: those that never saw Him in the one, have discovered Him in the other.”

The metaphor of the two books was widely used to affirm and preserve the distinctiveness of the natural sciences and Christian theology on the one hand yet to affirm their capacity for dialogue on the other. Both, it was argued, were written by God; might God be known, in different ways and to different extents, through each of these books individually, and even more clearly through reading them side by side? Although the concept of natural theology is complex and contested, many in the Renaissance viewed natural theology as a knowledge of God drawn from the “book of nature,” in contrast to a knowledge of God disclosed in the “book of Scripture.”

This metaphor served several important functions during the emergence of the natural sciences from about 1500 to 1750. In particular, it emphasized the importance of interpretation in the scientific investigation of the world. John Calvin’s Institutes of the Christian Religion was envisaged as a tool to help Christians discern the “bigger picture” enfolded within the biblical text. Early Reformed confessions of faith—such as the Belgic Confession (1561)—affirmed that “the universe is before our eyes like a beautiful book,” designed to encourage us to “ponder the invisible things of God” while simultaneously emphasizing that the Bible both clarified and extended this knowledge of God, setting it on a more reliable foundation.

The Scientific Revolution highlighted the need to do more than merely observe nature; the key objective was to understand its deeper structures, which often—as in the case of astronomer Johannes Kepler—involved the correlation of scientific and theological insights. Calvin’s “big picture” of the Christian faith explicitly encouraged a dialogue between the natural sciences and theology, recognizing both the parallels and divergences between the two books. “The knowledge of God, which is clearly shown in the ordering of the world and in all creatures, is still more clearly and familiarly explained in the Word.”

The metaphor of God’s two books rests on a fundamental belief that a God who created the world is also the God who is disclosed in and through the Christian Bible. Without this underlying and informing assumption, the two books need be seen as nothing more than two disconnected entities. The link between them is established and safeguarded by the Christian theological assumption of a creator God who is revealed in the Bible. The validity and intuitive plausibility of this metaphor during the Renaissance era reflect the cultural hegemony of Christianity at this time. Yet while this might now be seen to undermine the general cultural acceptability of this metaphor, it nevertheless remains a valid and valuable conceptual tool for the Christian community, as it seeks to frame and engage the natural sciences.

The metaphor of the two books originated within a historical context that sought to hold together the various elements of human knowledge, seeing this both as a cultural virtue and a spiritual duty. As has often been noted, one of the motivations for the serious scientific study of nature was a profound sense that this would enrich the believer’s appreciation of the beauty and wisdom of God as creator. Yet the specific historical location of this metaphor does not render it inapplicable to today’s discussions and reflections. It continues to offer an imaginative framing of the relation of Christianity and the natural sciences that has the potential to engage questions under consideration today, rather than restrict us to those that preoccupied Renaissance thinkers.

Recent thinking on metaphors has noted their potential to open up new ways of visualizing abstractions and framing relationships, rather than “freezing” us into any specific mode of understanding—such as that of a bygone age. We may thus retain this Renaissance metaphor, without being trapped in the controversies and limited scientific understandings of that age, provided we are attentive to the process of “reimagination” that is integral to any contemporary application of such a historic metaphor.

The metaphor of God’s two books has the potential to illuminate three significant aspects of the relation of Christianity and the natural sciences.

1. It emphasizes that the natural world and the Christian faith are distinct and that they must not be conflated or assimilated. Each has its own distinct topics and methods of investigation, representation, and systematization.

2. It creates an expectation of a meaningful, if limited, dialogue between science and Christianity that is grounded in a theological insight—namely, that God is the “author” of each of these two books. Although this theological insight was capable of being framed within a reductive and assimilationist deism, it remains an essentially Christian insight, suggesting that Christianity might itself provide a theological foundation or an informing theological context for this dialogue.

3. It underscores the point that the “reading” of either of these two books involves hermeneutical conventions. The interpreter of either book tends to approach it with certain preconceptions, which need, at least in principle, to be challenged by the process of engagement.

— Alister McGrath (DPhil, DD, DLitt, University of Oxford) is the Andreas Idreos Professor of Science and Religion, University of Oxford, director of the Ian Ramsey Centre for Science and Religion, and Gresham Professor of Divinity.

Taken from Three Views on Christianity and Science edited by Paul Copan and Christopher Reese. Copyright © 2020 by Paul Copan, Bruce Gordon, Alister McGrath, Christopher L. Reese, and Michael Ruse. Used by permission of Zondervan. www.zondervan.com.

Find Three Views on Christianity and Science at Zondervan or Amazon.

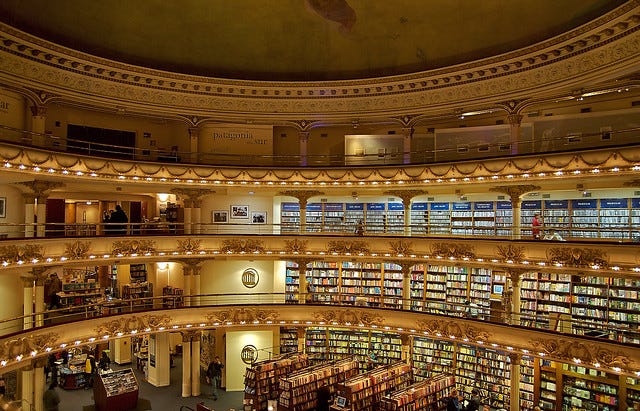

Image by Holger Schué from Pixabay

News

Ravi Zacharias Hid Hundreds of Pictures of Women, Abuse During Massages, and a Rape Allegation

Ravi Zacharias’s Books Pulled by HarperCollins After RZIM Investigative Report

5 Features That Made the Early Church Unique

Who Wrote the Pastoral Epistles? The Case for Traditional Authorship

Evangelical Colleges Consider the Future of Online Education After COVID-19

(*The views expressed in the articles and media linked to do not necessarily represent the views of the editors of The Worldview Bulletin.)

Subscribe

Join Christian thinkers like John Lennox, J. P. Moreland, Michael Licona, Sean McDowell, and Bobby Conway who look to The Worldview Bulletin for news, analysis, and encouragement for understanding and defending the Christian worldview!

“I find The Worldview Bulletin very stimulating and would encourage all thinking Christians to read it.”

— John Lennox, emeritus professor of mathematics, University of Oxford, emeritus fellow in mathematics and philosophy of science, Green Templeton College, author of 2084 (Zondervan)

“Staffed by a very respected and biblically faithful group of Evangelical scholars, The Worldview Bulletin provides all of us with timely, relevant, and Christian-worldview analysis of, and response to, the tough issues of our day. I love these folks and thank God for their work in this effort.”

— JP Moreland, distinguished professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology (Crossway)

“The Worldview Bulletin is a wonderful resource for those desiring to inform themselves in matters of Christian Apologetics. Learn key points in succinct articles written by leading scholars and ministers. All for the monthly price of a cup of coffee!”

— Michael Licona, associate professor of theology at Houston Baptist University and author of Why Are There Differences in the Gospels? What We Can Learn From Ancient Biography (Oxford University Press)

“The Worldview Bulletin is a wonderful resource for the church. It’s timely and helpful.” — Sean McDowell, associate professor in the Christian Apologetics program at Talbot School of Theology and author of The Fate of the Apostles: Examining the Martyrdom Accounts of the Closest Followers of Jesus (Routledge)

“Are you looking for a way to defend your Christian worldview? If so, look no further. At The Worldview Bulletin you’ll encounter world-leading scholars dispensing truth in a digestible format. Don’t miss out on this unique opportunity to engage in this meeting of the minds.”

— Bobby Conway, Founder of The One-Minute Apologist, author of Does God Exist?: And 51 Other Compelling Questions About God and the Bible (Harvest House)

Subscribe for only $2.50 per month and receive our monthly newsletter, access to our full archive of articles, and exclusive access to upcoming webinars with our contributors. You’ll also be supporting our work to inform, equip, and encourage Christian apologists around the world!

Book Deals

Look here for Faithlife’s free eBook of the Month. Visit here to get the Logos Free Book of the Month. You can download the free version of Logos which will allow you to access the monthly free books. Logos 9 is a great investment, though, and has tons of tools that make Bible study easier and richer.

The Epistemological Basis for Belief according to John’s Gospel by David A. Redelings, $2.99

The Harvest Handbook of Apologetics edited by Joseph M. Holden, $1.49

The Case for a Creator: A Journalist Investigates Scientific Evidence That Points Toward God by Lee Strobel, $2.99

Investigating the Resurrection of Jesus Christ: A New Transdisciplinary Approach by Andrew Loke is available free on Amazon.

Loving God with Your Mind: Essays in Honor of J. P. Moreland edited by Paul Gould and Richard Davis, $2.99

Does God Exist? by William Lane Craig, $3.99

Lost In Transmission?: What We Can Know About the Words of Jesus by Nicholas Perrin, $3.99

The Missing Gospels: Unearthing the Truth Behind Alternative Christianities by Darrell Bock, $4.99

Think Christianly: Looking at the Intersection of Faith and Culture by Jonathan Morrow, $4.99

God and Stephen Hawking: Whose Design Is It Anyway? by John Lennox, $4.45

God Under Fire: Modern Scholarship Reinvents God ed. by Douglas Huffman and Eric Johnson, $4.49

The Philosophy of Saint Thomas Aquinas: A Sketch by Stephen L. Brock, $2.99

Five Views on Apologetics edited by Steven B. Cowan, $6.49

Mere Apologetics: How to Help Seekers and Skeptics Find Faith by Alister McGrath, $1.49

Mere Christianity by C. S. Lewis, $1.99

The Harvest Handbook of Bible Lands: A Panoramic Survey of the History, Geography and Culture of the Scriptures edited by Steven Collins and Joseph M. Holden, $1.99

The Harvest Handbook of Bible Prophecy: A Comprehensive Survey from the World's Foremost Experts edited by Ed Hindson, Mark Hitchcock, and Tim LaHaye, $1.99

The Gospel According to Satan: Eight Lies about God that Sound Like the Truth by Jared Wilson, $2.99

What's Best Next: How the Gospel Transforms the Way You Get Things Done by Matt Perman, $3.99

Jesus on Every Page: 10 Simple Ways to Seek and Find Christ in the Old Testament by David Murray, $4.99

God's Love: How the Infinite God Cares for His Children by R. C. Sproul, $2.99

The Flourishing Teacher: Vocational Renewal for a Sacred Profession by Christina Lake, $5.99

Pictures at a Theological Exhibition: Scenes of the Church's Worship, Witness and Wisdom by Kevin Vanhoozer, $4.99

Culture Care: Reconnecting with Beauty for Our Common Life by Makoto Fujimura, $4.99

Marriage and the Mystery of the Gospel by Ray Ortlund, $3.99

The Pilgrim’s Regress by C. S. Lewis, $3.99

The Reformation by Diarmaid MacCulloch, $4.99

(These deals were good at the time of writing, but prices or offers may change without notice.)