Bulletin Roundtable

In this multipart Roundtable, our three regular contributors are exploring the transcendentals—fundamental attributes of being that in much Christian thinking consist of truth, goodness, and beauty. Last week, Paul Copan did a deep dive into the transcendental of truth. Today, David Baggett takes us on a tour of the trascendental of goodness.

David Baggett

Goodness

The topic of goodness, like that of truth and beauty, is of infinite richness, particularly if the good and God himself are as intimately tied together as one like Augustine thought. If God himself is the ultimate good, then it makes perfect sense that it’s no easy matter to say just what goodness is, for the ultimate good would be nothing less than God himself, who defies our finite understandings and escapes our ability fully to define or comprehend. This is why Robert Adams suggests that, if such a picture is remotely accurate, we should retain a “critical stance” toward various and sundry accounts of goodness, because they are unlikely to be the whole picture.

Nowadays goodness tends to be treated in more domesticated and deflationary ways. Goodness is that which conduces to our flourishing, we hear it said, or goodness is what promotes social harmony. Or, following Aristotle, goodness is said to pertain to the function of something. A good car provides reliable transportation, for example. For a long while now, though, I have thought such an Aristotelian depiction of the good inseparable from a more Platonic conception—what is good for us as human beings, for example, seems impossible to divorce from what is good in and of itself.

Although it makes sense to say that something is good to the extent it performs its function, a further question then always should be asked: Is that function a good thing? This is an especially important question to ask if we wish to think about moral goodness in particular. Of course goodness is broader than moral goodness, but moral goodness is a quite important part of goodness. And in fact, in many contemporary discussions, quite a bit of confusion reigns when it comes to moral and nonmoral goodness.

For example, we often hear that pain is bad, and surely it is. But it’s not morally bad per se. It is nonmorally bad. What’s morally bad is the needless infliction of pain for no good reason. It tends to be people who are morally good or morally bad. Immanuel Kant recognized this distinction when he distinguished between badness and evil. In plenty of contexts these terms are used interchangeably, but he used the distinction to highlight the difference between something that produces bad consequences and something distinctively and robustly, even perniciously, immoral. Inadvertently missing the nail with the hammer and hitting my thumb instead is surely the former, but hardly the latter.

Students sometimes insist on the need for a pithy, succinct account of goodness, but I suspect such a request is more difficult than it may seem. Besides getting clarity on whether the goodness to be defined is axiological or metaphysical, moral or nonmoral, and whether it’s what’s good in itself or good for us, still other questions press. Suppose we try to make our task simpler by delimiting the discussion to what is morally good for us. Rather than settling the matter, that step only raises new questions to consider. What sorts of creatures are we? What is good for us vitally depends on anthropology, who we are. It also depends on what range of goods there are. Is what is good for us merely the meeting of our physical needs—or are we spiritual and affective, aesthetic and relational beings as well? Is our deepest good fellowship with God and learning to love God and neighbor as ourselves? Is that the richest source of our deepest joy? Christianity would suggest just such an answer.

Besides questions of anthropology, answers to what ultimate goodness consists in also depend on the nature of ultimate reality. This means that one’s conception of God is also at play here. A warped understanding of who God is will invariably diminish one’s conception of ultimate goodness. So to insist that we provide a quick and easy answer to what goodness is without realizing that the right answer depends on both an accurate picture of who we are and who God is will relegate one’s answers to superficiality. Few topics are handled so poorly without due consideration of issues of transcendence and the sacred.

As a moral apologist I find the topic of goodness endlessly fascinating, for a number of reasons, one of which is that, like beauty, there is something ineliminably experiential about it. Those without the requisite taste of goodness in their lives are less likely to be moved by something like a moral argument for God’s existence, just as those without the requisite experience of beauty are less likely to be persuaded by an aesthetic argument.

This is also why it is a powerful reminder to prospective apologists, as they strive to be salt and light in this world, to offer not just arguments but their very lives as evidence of the truth of the gospel. Like Fred Rogers would often say, our job is to make goodness attractive. And here again we see the truth that goodness and beauty are, as Plato could see, flip sides of the same coin. For goodness is, by its very nature, beautiful, which is why we find ourselves so drawn to it (and them).

I recently heard it said God doesn’t want us happy, but holy. I think such a sentiment is deeply misguided. Surely God wants us holy—as he is holy. He’s in the process of sanctifying us through and through, making us good, the people we were meant to be, the distinctive reflections of Jesus that God had in mind when he created us. But in that sanctified life, the joy of the Lord is our strength; there’s the deepest fulfillment of which we are capable, the richest joy we can experience as we allow the divine life to take hold within us. We are made for fellowship, and we are told that the glory to come will render all the present sufferings insignificant by comparison. We are meant for goodness and holiness, it’s true, and these do have a sort of primacy over happiness, but ultimately there is not the slightest tension between them. Rather than mutually exclusive, they are ultimately of a piece. We were meant for both goodness and eternal joy. The beatific vision for Christ followers could not produce anything less.

— David Baggett is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Center for Moral Apologetics at Houston Baptist University. He is the author or editor of about fifteen books, most recently The Moral Argument: A History written with Jerry Walls.

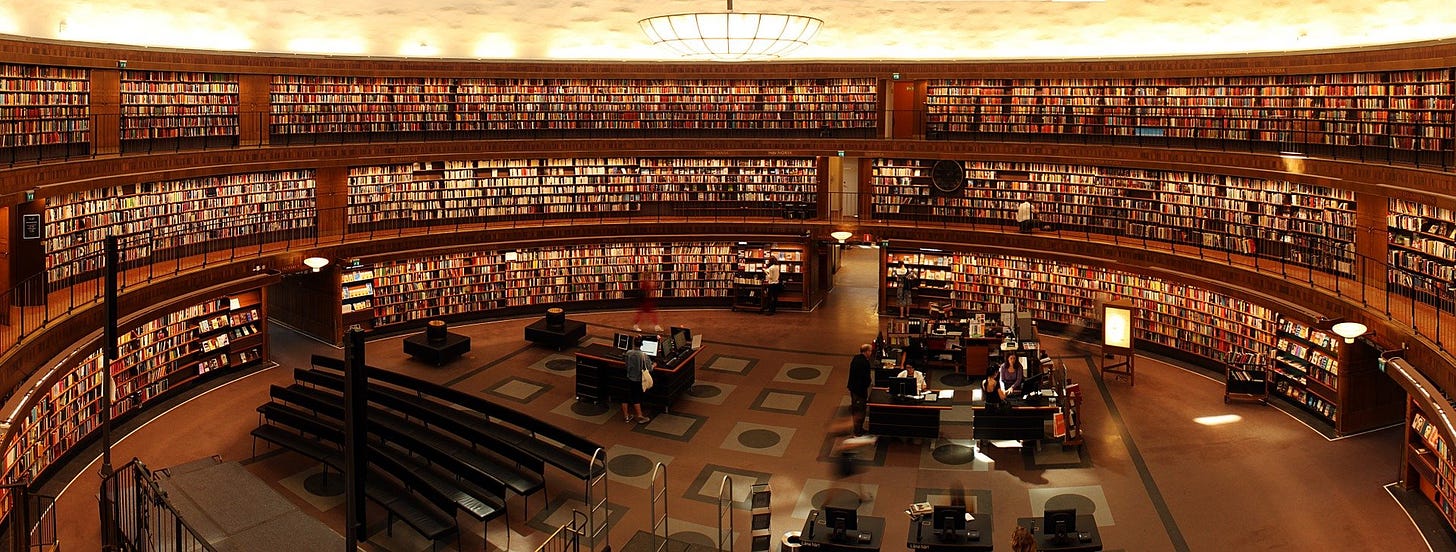

Image by James Wheeler from Pixabay

Recommended Resource

One of the defining characteristics of Christian theism is its understanding of the nature and attributes of God. As one studies the doctrine of God, a number of questions naturally arise: Does God change? Does God have emotions? Does everything occur as God wills? Is God entirely good and loving? How can God be one God and three persons?

Skeptics frequently charge that one or more of God’s attributes is incoherent, or that they contradict one another. Believers often wonder what it means, for example, that God is unchanging or all-loving, and how they should understand God in light of these qualities.

Given the importance of these questions for the Christian worldview, we highly recommend John C. Peckham’s recent book on this topic, Divine Attributes: Knowing the Covenantal God of Scripture. Drawing on Scripture, theology, and philosophy, Peckham explains each attribute in detail, engages with the most important scholarship related to it, and shows how each can be understood in a theologically faithful and philosophically robust manner.

See our recent excerpt from the book titled The God of the Philosophers?

“This volume on the divine attributes and ‘covenantal theism’ is a superb work of theology. It is thorough, nuanced, and balanced. As in his other works, Peckham is both winsome and bold: he winsomely engages important age-old and more recent theological conversations and controversies, and he boldly challenges certain theological positions while confidently articulating and defending the considerable merits of covenantal theism.”

— Paul Copan, Pledger Family Chair of Philosophy and Ethics, Palm Beach Atlantic University; author of Loving Wisdom: A Guide to Philosophy and Christian Faith

“Divine Attributes will be a game changer for debates about the nature of God. Strict classical theists and open theists must deal with the powerful biblical case that Peckham presents. If you are looking for a theology text that is faithful to the biblical witness and sensitive to the philosophical challenges that arise from thinking about the nature of God, then Divine Attributes is the book for you.”

— R. T. Mullins, Helsinki Collegium for Advanced Studies

Find Divine Attributes: Knowing the Covenantal God of Scripture at Baker, Amazon, and other major booksellers.

*This is a sponsored post.

News

New “Three Views” Book Explores the Relationship of Faith and Science

The Turning Tide of Intellectual Atheism

Twenty-Five Things Everyone Used to Understand

The Neglected Ministry of Asking Questions

When Marriage Becomes a Private Matter

Supreme Court rejects appeal by Christian grandma florist fined for refusing same-sex wedding

Podcast: The Life and Mind of C. S. Lewis (Harry Lee Poe)

Video: How Should Christians & Skeptics React to Pascal's Wager?

Video: Is the Gospel of John Historically Reliable? (Dr. Lydia McGrew)

Video: Is There a Conflict Between Morality Being Objective and Changing Over Time?

(*The views expressed in the articles and media linked to do not necessarily represent the views of the editors of The Worldview Bulletin.)

Book Deals and Resources

Look here for Faithlife’s free eBook of the Month.

Visit here to get the Logos Free Book of the Month. You can download the free version of Logos which will allow you to access the monthly free books. Logos 9 is a great investment, though, and has tons of tools that make Bible study easier and richer. New users can get 50% off of the Logos 9 Fundamentals package, which discounts it to $49.99.

Get a second free book of the month here.

See the Logos Monthly Sale for dozens of good deals, as well as their current sale on highly rated commentaries.

Audiobook: The Christian in the World by C. S. Lewis, $2.99 (19 of Lewis’s essays on various subjects)

Audibook: Scripture Alone by James R. White, $2.99

Audiobook: The Call by Os Guinness, $3.99

Audiobook: Silence and Beauty by Makoto Fujimura, $1.99

Neo-Aristotelian Perspectives on Contemporary Science is available free as an open-access book (download the full book using the “Download” button on the right side of the screen, opposite the cover image).

July eBook Sale – 51 Eerdmans Titles Up to 94% off

2084: Artificial Intelligence and the Future of Humanity by John Lennox, $2.99

Holy Sexuality and the Gospel: Sex, Desire, and Relationships Shaped by God's Grand Story by Christopher Yuan, $1.99

The Problem of Pain by C. S. Lewis, $1.99

A Grief Observed by C. S. Lewis, $1.99

The Story of the Cosmos: How the Heavens Declare the Glory of God edited by Paul Gould and Daniel Ray, $4.99 in print from Christianbook.com.

Original Sin and the Fall: Five Views edited by J. B. Stump and Chad Meister, $5.99

Evangelism and the Sovereignty of God by J. I. Packer, $3.19

A Little Book for New Bible Scholars by E. Randolph Richards and Joseph R. Dodson, $3.99

The Missing Gospels: Unearthing the Truth Behind Alternative Christianitiesby Darrel Bock, $4.99

Theological Theodicy by Daniel Castelo, $2.99

A Master Class in Christian Worldview

Learn from world-class Christian apologists, scholars, and philosophers, and support our work of making these resources available, all for only $2.50 per month. There’s no obligation and you can easily cancel at any time. Be equipped, informed, and encouraged!

“The Worldview Bulletin is a must-have resource for everyone who’s committed to spreading and defending the faith. It’s timely, always relevant, frequently eye-opening, and it never fails to encourage, inspire, and equip.”

— Lee Strobel, New York Times bestselling author of more than forty books and founding director of the Lee Strobel Center for Evangelism and Applied Apologetics

“Staffed by a very respected and biblically faithful group of Evangelical scholars, The Worldview Bulletin provides all of us with timely, relevant, and Christian-worldview analysis of, and response to, the tough issues of our day. I love these folks and thank God for their work in this effort.”

— JP Moreland, distinguished professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology (Crossway)