Top 30 Apologetics Books (#10): Blaise Pascal, Pensées

Plus: Talking With Dawkins by Justin Brierly

Quotable

From Kant's perspective, therefore, there may be a God, but there is nothing we can really say about him as to his being an object of our knowledge [since he exists outside of the realm of sense experience]. So surely, Kant argued, we cannot produce any argument, much less demonstrative proof, that God exists. While Kant did believe in the existence of God, he averred that God must be a postulate of practical rather than pure reason (that is, ethics rather than epistemology). Kant was an ethicist, and he believed he needed the existence of God to ensure the moral governance of the world. If there is no God, then everyone might live as they please without fear of a final judgment. Kant believed that religion had one main purpose: to furnish moral foundations and education for society. In his most significant book on religion, Religion within the Limits of Reason Alone, Kant relegated religion to the ethical realm. Authentic religion, including true Christianity, amounted to living a life in harmony with rationally discernible duty.

Given the indispensability of genuine moral accountability in the universe, Kant claimed that there had to be a God. However, we cannot prove this because God lies in the noumenal realm, far beyond what our experience can know. As a result, God is effectively taken out of metaphysics and thus debarred from demonstration, knowability, and meaningful discourse. Ironically, Kant viewed this as a major step forward for Christianity: "I have therefore found it necessary to deny knowledge, in order to make room for faith." So although Christians can never know God and other realities beyond the human senses, they can still believe in them. Hence Kant instigated the infamous distinction between knowledge and faith. This Kantian maneuver unwittingly paved the way for what we will encounter in chapter 19, namely, the death of God theologies. For suppose the best theists can do is to postulate that God exists because they need God to ensure the moral governance of the world. Then it will not be long before God is seen as even more transcendent to the point where theologians will claim that God is totally beyond our knowledge and our being able to say anything about him. And if this is the case, we might as well say that there is no God or, at least, that God as we thought of him certainly must not exist.

— Kirk R. MacGregor, Contemporary Theology: An Introduction—Classical, Evangelical, Philosophical & Global Perspectives (Zondervan, 2019), 21.

Note: Below, Dr. Rob Bowman continues his series on the 30 most important apologetics books in church history. See his earlier posts in previous weeks of Useful Things.

#10: Blaise Pascal, Pensées (1669)

One of the most brilliant and original thinkers in human history is the French polymath Blaise Pascal (1623-1662). Despite dying before reaching the age of 40, Pascal made significant contributions to mathematics, physics, technology, literature, theology, and philosophy. Pascal was an early advocate of what was dubbed Jansenism, a Catholic movement that emphasized a staunchly Augustinian understanding of human nature, sin, and salvation that the Catholic hierarchy regarded as uncomfortably close to Calvinism. During his last years, he worked on a book defending the faith that was incomplete when he died. His notes were gathered together and published as Pensées (“Thoughts”). To this day there is dispute among scholars regarding the best arrangement of these notes, which are published as a loose collection of numbered sections of varying lengths.

In number 60 Pascal summarized what were evidently to be two major points developed in his work. The first part he entitled “Misery of man without God” or “That nature is corrupt. Proved by nature itself,” and the second part “Happiness of man with God” or “That there is a Redeemer. Proved by Scripture.” Later he noted that “the Christian faith goes mainly to establish these two facts, the corruption of nature, and redemption by Jesus Christ” (194).

The most famous passage in the Pensées is known as Pascal’s wager: “Let us weigh the gain and the loss in wagering that God is. Let us estimate these two chances. If you gain, you gain all; if you lose, you lose nothing. Wager then without hesitation that He is” (233). Contemporary philosophers have given the wager argument considerable attention, and there has been much debate about it. In context, Pascal’s wager appears to be a recommendation to unbelievers to try the Christian faith—to enter into the experience of the faithful as a way to faith. If we refuse to believe and act unless we have certainty, Pascal reminds us, we will “do nothing at all, for nothing is certain” (234).

Pascal regarded attempts “to prove Divinity from the works of nature” in arguments with unbelievers to be counterproductive (242–245). Although he denied that faith rests on proofs, he affirmed that proofs are available and offered a brief list of a dozen proofs. These include the establishment of the Christian religion despite its being contrary to human nature; the changed life of a Christian; the biblical miracles in general; the miracles and testimonies of Jesus Christ, the apostles, Moses, and the prophets; the Jewish people; biblical prophecies; and other evidences (289). The rest of the Pensées elaborates on these evidences, which provide confirmation of the claims of Jesus Christ in Scripture: “Apart from Jesus Christ, we do not know what is our life, nor our death, nor God, nor ourselves. Thus without the Scripture, which has Jesus Christ alone for its object, we know nothing” (547). The voice of God is clearly heard in Scripture, and for Pascal, the Christ of Scripture is the real proof of Christianity.

—Rob Bowman Jr. is an evangelical Christian apologist, biblical scholar, author, editor, and lecturer. He is the author of over sixty articles and author or co-author of thirteen books, including Putting Jesus in His Place: The Case for the Deity of Christ, co-authored with J. Ed Komoszewski. He leads the Apologetics Book Club on Facebook.

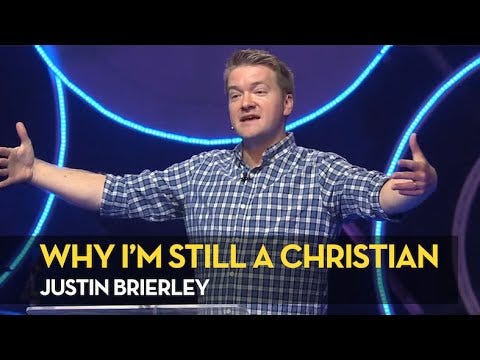

Talking with Dawkins

by Justin Brierley

Christians need to reboot the art of good conversations with sceptics, says Justin Brierley

The room was abuzz with conversation as the canapés and wine circulated. But my heart was in my mouth as I walked up, microphone recorder in hand, to introduce myself to the man at the centre of the throng. “Don’t fluff this, Justin”, was all I was thinking.

The person I was about to interview was atheist biologist Richard Dawkins, the author of the bestselling book The God Delusion (Bantam, 2006). He had just taken part in a high-profile public debate at the Oxford’s Natural History Museum on the existence of God with professor John Lennox, a Christian mathematician.

Now at the after-show party (and whether he was in the mood or not for another debate) I plunged straight in, cross-examining Dawkins on some of the issues that had been raised. Wasn’t his view of a purposeless universe a bit bleak? Can concepts like love be reduced to chemical processes? What about cosmology and morality?

Is Rape Wrong?

This is perhaps where the most interesting part of our discussion happened. When I pressed the professor on whether we can really believe that morality is derived only from his concept of god-less, undirected evolution alone, his answer was revealing.

Me: But if we’d evolved into a society where rape was considered fine, would that mean that rape is fine?

Dawkins: I don’t want to answer that question. It’s enough for me to say that we live in a society where it’s not considered fine. We live in a society where selfishness, failure to pay your debts, failure to reciprocate favours is regarded askance. That is the society in which we live. I’m very glad—that’s a value judgement—glad that I live in such a society.

JB: But, when you make a value judgement don't you immediately step yourself outside of this evolutionary process and say that the reason this is good… is that it's good. And you don't have any way to stand on that statement?

RD: My value judgement itself could come from my evolutionary past.

JB: So therefore it's just as random, in a sense, as any product of evolution.

RD: You could say that. In any case, nothing about it makes it more probable that there is anything supernatural.

JB: Ok. But ultimately, your belief that rape is wrong is as arbitrary as the fact that we've evolved five fingers rather than six.

RD: You could say that, yeah.

Making Sense of Our Morality

I was recording our conversation for an edition of my radio show and podcast Unbelievable?, a show which has been featuring dialogues between Christians and non-Christians for over ten years. After the show aired, it was this part of our conversation that was picked up by many commentators, both atheist and Christian.So, what was so significant about this moment?

For me it highlighted that even the world’s most famous atheist could not account for the nature of his moral beliefs on the basis of biology alone.

By saying that his feelings about rape are simply a result of his biological and social conditioning, Dawkins affirmed that his moral beliefs are as undirected and arbitrary as any other part of the natural world. Yet you, me and Dawkins all know that rape really is wrong (which, I think, is why he didn’t want to answer my first question). Not because it happens to be where our culture has landed in its evolutionary history, because we know deep down that’s not how humans should treat one another.

Yet, such a belief in things being really right and wrong, that there is a way things should be, and that humans have intrinsic value, only makes sense if something beyond evolution, culture and our material world can ground it. Dawkins’ response confirmed again the power of 'the moral argument for God'. Our sense that there is a realm of objective laws of good and evil only makes sense if there is a moral lawgiver.

It was the same argument that had convinced another Oxford professor, C. S. Lewis, to abandon his atheism eighty years ago when he wrote, "My argument against God was that the universe seemed so cruel and unjust. But how had I got this idea of just and unjust? A man does not call a line crooked unless he has some idea of a straight line. What was I comparing this universe with when I called it unjust?"

Conversations Matter

It was a conversation with friend and fellow Oxford don J. R. R. Tolkien that finally led Lewis to embrace Christianity. I too have found that conversations are often helpful for getting to the bottom of what someone really believes about reality. Sadly, Christians often avoid interactions with atheists and sceptics, fearing they won't be able to answer the objections they might encounter. But, in over ten years of talking with atheists on my radio show, I've realised that Christian have nothing to fear.

Many atheists hold to just as many 'faith' assumptions as Christians, because they believe in 'naturalism'. This is a view of reality in which the universe appeared from nowhere and is heading nowhere. In which life, against all the odds, is just a happy cosmic fluke. Beauty, purpose, love, goodness, evil and everything else that gives life a sense value, is ultimately an illusion.

But I see a very different universe to atheists like Dawkins. Where he sees only matter in motion, acting according to the blind physical forces of nature, I see a world of real meaning, right and wrong, hope and truth, justice and injustice. We are both called to give an account of why we see things so differently, and ask whose story of reality fits best with our human experience.

It turns out that the Christian story, in which God created the cosmos, makes sense of the incredible order of a universe finely-tuned for the human life that inhabits it. Likewise, the Christian story, in which we are made in the image of God, makes a lot better sense of our feeling that human life has intrinsic dignity and worth. And it turns out that the universal human longing for meaning, purpose and the transcendence makes sense in light of a story in which God reaches across the cosmos to come to us in person, and show us what hope looks like.

Scripture also reminds us of the value of conversations with those who are sceptical. "Always be prepared to give an answer to everyone who asks you to give the reason for the hope that you have. But do this with gentleness and respect" (1 Peter 3:15). I'm not going to pretend that my ten-minute chat with Dawkins convinced him of that hope. But for the many people who have heard it since, and who are undecided about which story of reality to believe, it may just turn out to be a piece of the puzzle that leads them towards God. And that's the great thing about conversations—you never where they might lead.

*This article was first published in Preach magazine, www.preachweb.org.

Justin Brierley's book Unbelievable? Why After Ten Years of Talking with Atheists, I'm Still a Christian (SPCK) is available now. www.unbelievablebook.co.uk

Also, check out Unbelievable? The Conference taking place in Los Angeles on October 12th. Speakers include Justin Brierley, John Lennox, J. Warner Wallace, and Mary Jo Sharp, among others.

In the video below, Justin talks about the importance of spiritual conversations and his work on the Unbelievable? radio show.

News*

Explainer: The conundrum in the UK over no-deal Brexit

Hong Kong Christians: Bill's removal not enough

Were the Earliest Christians Only Concerned about Oral Tradition?

10 New Suggested Readings for Budding Apologists

The New Thought Roots of the Prosperity Gospel

The Next Stage in Evangelism and Apologetics: Interview with Lee Strobel

French-Ahmari: A Report From The Scene

[Sohrab Ahmari and David French met to debate the future of cultural conservatism, moderated by Ross Douthat and hosted by the Institute for Human Ecology at the Catholic University of America.]

Colorado Doctor Fired after Suing Catholic Hospital over Assisted Suicide

(*The views and opinions expressed in the articles, videos, podcasts, and books linked to do not necessarily represent the views of the editors of The Worldview Bulletin.)

eBook, Audiobook, and Software Deals

Note: These deals were valid at the time this edition was written, but prices may change without notice. The same deals are often available on Amazon sites in other countries.

eBooks

Faithlife Ebooks, a division of Logos Bible Software, gives away a free ebook every month. September’s book is The Radical Disciple by John Stott. You can also pick up two other John Stott books for $3.99 each. You can read the ebooks using their app, or in Logos Bible software (free version here).

The Cross and Salvation: The Doctrine of Salvation by Bruce Demarest - $2.99

What Does the Bible Say About Suffering? by Brian Han Gregg - $4.99

Why Believe?: Reason and Mystery as Pointers to God by C. Stephen Evans - $1.99

The Gospel of the Lord: How the Early Church Wrote the Story of Jesus by Michael Bird - $3.99

The Inspiration and Interpretation of Scripture: What the Early Church Can Teach Us by Michael Graves - $3.99

The Missing Gospels: Unearthing the Truth Behind Alternative Christianities by Darrell Bock - $0.99

Audiobooks

The Four Loves by C. S. Lewis - Narrated by C. S. Lewis from the vintage BBC recordings - $4.99

Software

The Logos free book for September is James (Zondervan Exegetical Commentary on the New Testament) by Craig Blomberg and Mariam Kamell. For an additional $1.99, you can also pick up Colossians and Philemon in the same series, and for $4.99 can get 1, 2, and 3 John (see all three at the link above).

Video

On Marty Sampson's doubts. What's going on? (Mike and Debbie Licona)

Why Joe Rogan is WRONG About Christianity (Capturing Christianity)

Philosopher of Science Stephen C. Meyer Explores The Exciting Theory of Intelligent Design

Is Faith Blind? (Inspiring Philosophy)

Gregory Ganssle - Classical Arguments for God?

Audio

Re-enchanting the Universe with Dr. Paul M. Gould

Computer Engineer Bob Marks Discusses the Perils and Promise of AI

Ben Shapiro and a Reasonable Faith Update

Ken Samples on Classic Christian Thinkers

Following Jesus in Digital Babylon (with David Kinnaman)

Book Highlight

*Unless otherwise noted, descriptions are those provided by the publisher, sometimes edited for brevity.

Accessible and comprehensive, Contemporary Theology: An Introduction by professor and author Kirk R. MacGregor provides a chronological survey of the major thinkers and schools of thought in modern theology in a manner that is both approachable and intriguing.

Unique among introductions to contemporary theology, MacGregor includes:

Evangelical perspectives alongside mainline and liberal developments

The influence of philosophy and the recent Christian philosophical renaissance on theology

Global contributions

Recent developments in exegetical theology

The implications of theological shifts on ethics and church life

Contemporary Theology: An Introduction is noteworthy for making complex thought understandable and for tracing the landscape of modern theology in a well-organized and easy-to-follow manner.

Kirk R. MacGregor (PhD, University of Iowa) is assistant professor and chair of the Department of Philosophy and Religion at McPherson College in McPherson, Kansas. He is the author of several scholarly works including A Molinist-Anabaptist Systematic Theology.

Praise for Contemporary Theology

"In Contemporary Theology Kirk MacGregor skillfully acquaints readers with the principal thinkers and schools of thought in Christian theology over the past two hundred years, both inside and outside evangelicalism. MacGregor beautifully discloses how the renaissance in philosophy of religion over the past half-century has shaped many of the most creative and constructive strides in theology today. I heartily recommend this book."

— William Lane Craig, research professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology, and professor of philosophy, Houston Baptist University

“Contemporary Theology: An Introduction will assuredly--and quickly--become an indispensable addition to the required reading list for undergraduate and graduate courses on Christian theology and Christian ethics. As in all his publications, Professor MacGregor combines comprehensive and context-driven historical analysis with superlative writing skills. Difficult concepts are presented in a clearly-written, crisp, and engaging style. For the general reader interested in the positive impact of Christian ethics on our fragmented and contentious world, your understanding of the ongoing cultural struggle for ethical assurances, drawn from the long history of Christian theology, will be exponentially enhanced. Highly recommended!"

— John K. Simmons, professor emeritus of religious studies, Western Illinois University

Available from Amazon, Zondervan, and other online booksellers.

If you enjoy Useful Things, become a subscriber and receive our monthly newsletter, The Worldview Bulletin. Subscribe now and gain immediate access to our August issue as well as our full archive of past issues. In the August issue:

Paul Copan completes his series on the inescapability of design in science

Paul Gould explains the purpose of art

We interview Daniel Ray on the book The Story of the Cosmos

Edgar Andrews concludes his series on the nature of a biblical worldview

Plus news, book deals, helpful resources, and conferences!