Natural Law: An Introduction, Part 3

By Nicholas K. Meriwether

*Note: Part 1 and Part 2 of this series can be found at these locations.

Natural law is that apprehension of the conscience which distinguishes sufficiently between just and unjust, and which deprives men of the excuse of ignorance, while it proves them guilty by their own testimony.

— John Calvin, Institutes, Bk. II, Chap. 2, xxii.

In Part 2 of this series, we looked at the content of natural law, which is the Ten Commandments (aka the Decalogue) and the basic design of human nature. One might think that we learn the Ten Commandments by reading the Bible. But if the Bible were the only source of moral knowledge, only a very small percentage of the human race would know right from wrong. And as we will see, the Bible itself doesn’t claim that people know right from wrong only by reading it. But how do we explain how we know the Decalogue? In Part 3, we turn to how we know right from wrong.

To add to the difficulty, doing the right thing often occurs in a bewildering context in which justice doesn’t seem to prevail (Jer. 12:1; Hab. 1:13). Many suffer and die for doing the right things. So we can’t base moral knowledge upon who lives a long and contented life, or a short, difficult one.

Not only do we often fail to see justice prevail, we may find ourselves in circumstances in which being moral is dangerous. Austrian author Stefan Zweig describes a harrowing situation in post-WWI Salzburg during a period of rampant inflation, where in order to survive, one had to be immoral.

A man who respected the food rationing system starved; only one who disregarded it brazenly could eat his fill. A man schooled in bribery got ahead; he who speculated, profited. If a man sold appropriately to the buying price, he was robbed, and if he calculated carefully, he was cheated. Standards and values disappeared during this melting and evaporation of money; there was but one virtue: to be clever, shrewd, unscrupulous, and to mount the racing horse rather than be trampled by it.[1]

The situation Zweig describes challenges those who believe moral knowledge derives from our environment. Saying we obtain moral knowledge from the society or culture we live in has disturbing implications—not just in periods of civilizational collapse as in post-war Austria, but also in contexts in which being immoral is ingrained in the culture we inhabit, such as a street gang, the Mafia, or a corrupt society (Gen. 19). Moral knowledge must have a more stable basis than what we experience most of the time.

Moral Knowledge

So we can’t simply assume people know, we must at least explain how they know, and especially, why they so often violate what they know, which complicates the question even more.

Yet it is here that natural law by itself is inadequate. We see this most clearly in Aristotle’s wrestling with moral responsibility in the Nichomachean Ethics. He does in fact claim that every human being is responsible for any wrong he commits, unless his action is forced by something outside himself (a blast of wind), or he’s ignorant of the circumstances (1110b25). Yet his explanation of how it is that people can be held responsible is through an indirect argument: If we say that vice isn’t our fault, then neither is virtue, yet this seems preposterous. He concludes:

If doing the noble and the shameful things is up to us, and similarly also not doing them—and this… amounts to our being good or bad—it is, therefore, up to us to be decent or base. (1113b)

Yet if we’re responsible, if we can’t claim being moral is beyond our ability, doesn’t this mean that we must inevitably know what we should do? But how do we come to know it? Aristotle never explains. For an explanation, we must turn to divine revelation. This underscores what I said earlier, that natural law should not be seen as somehow sufficient without Scripture.

According to Scripture, God designs us in such a way that moral knowledge is natural. In Romans 2:14-16, Paul says the moral law is “written on our hearts,” that is, through the conscience, described by Calvin as “a certain knowledge of the law by nature,”[2] so that all are without excuse. But in what way? How exactly does God do this? What is the nature of the moral knowledge God provides?

We must add yet another layer to an already complex topic by acknowledging that we seem to know naturally (without being taught) what we should do, yet we violate this frequently. In fact, we can violate it so much that our conscience can become “seared,” or so insensitive that we no longer feel guilt for our crimes, like a hit man for the Mafia or a sex trafficker. But do we then lose all moral knowledge, despite its being written on our hearts?

To greatly simplify a centuries-long development within medieval philosophy, our conscience can be divided into two parts or functions, the part that knows, and cannot fail to know, the moral law, which came to be called “synderesis,” and the part that applies it, or “conscience” proper. (Jerome [342-420] introduced the distinction between synderesis and conscience, although his term synderesis adapts the word for “conscience” in Greek.) Through synderesis, we know the “primary precepts,” the foundations of morality. These include that we should pursue good and not evil, that we should love God, and the Golden Rule—love your neighbor as you love yourself, or “Do unto others what you would have them do unto you” (Matt. 7:12).

From these most general precepts, we infer the content of the Ten Commandments, known as the “secondary precepts.” As you can see, the First Table, Commandments 1-4, derive from loving God above everything else (You shall have no other gods before me; You shall not make for yourself a carved image or bow down to or serve such images; You shall not take God’s name in vain; and You shall observe the Sabbath.) The Second Table derives from loving one’s neighbor (You shall honor your father and your mother; You shall not murder; You shall not commit adultery; You shall not steal; You shall not lie; You shall not covet).

The Practical Syllogism

When we think in moral terms, which should be most if not all the time (even math requires honesty and diligence), synderesis supplies the general precept, and conscience “legislates,” that is, directs us to apply the general precept to our circumstances. What should follow is either an action in conformity with the dictates of conscience, and so a sense of moral approbation, or, if conscience is violated, regret and guilt.

To explain this phenomenon of acting on a general premise, Aristotle developed what has come to be called the “practical syllogism.” While it may at first appear unnecessarily formal and clumsy, it arguably captures what the mind undergoes instantaneously. In addition, it helps explain what goes wrong when people act immorally.

Let’s say that on his last day at work before moving to another state, Jim finds several hundred dollars in cash in a remote location, and realizes that he could pocket the cash without fear of being caught—no one will ever know who took it. However, he has “scruples,” meaning he is hesitant because he knows it’s wrong to steal. The syllogism would be as follows:

Major premise: It is wrong to steal.

Minor premise: To take this cash would be stealing.

Conclusion: Jim does not take the cash (and reports it instead).

If Jim’s conscience and his character are in good working order, his “conclusion” will be not to take the cash. If they’re not, but he has at least some decency, he will feel guilty about taking it. However, if he’s given to stealing and his conscience is seared, he may be “ignorant” of what he should do, in which case his major premise might be, “Finders keepers, losers weepers.” Yet even if his major premise is the product of a seared conscience, synderesis prevents him from being completely isolated from moral knowledge, and thus, makes him morally responsible. So a person can willingly do wrong, yet at the same time, know what he should do. And of course, we often say of any crime or immoral action, no matter how habitual, that the person committing it “should have known better.”

The practical syllogism also helps us analyze what are otherwise potentially confusing aspects of the moral life. We’ve all experienced various forms of temptation, and all of us at some point succumb, unless and until we gain the fortitude to resist through grace and determination. We can also gain virtue, which enables us to act morally without painful struggle. Aristotle calls a person “temperate” whose virtue makes doing the right thing painless (arguably an impossible standard). The continent person succeeds, but struggles like Jim. The incontinent person struggles like the continent person, yet fails, and afterwards feels regret. Finally, the intemperate person’s conscience is seared, so he acts on the wrong major premise, and has no scruples about it. For Aristotle, this person can’t be “cured,” because he doesn’t desire to do the right thing, and has lost his knowledge of what it is to do the right thing. However, this knowledge is never completely lost, because synderesis, the “light of conscience,” prevents this from happening.

Notes

[1] Stefan Zweig, The World of Yesterday, trans. Benjamin Huebsch and Helmut Ripperger (Plunkett Lake, 2011, Kindle ed.), 325. I modified the translation from the original German.

[2] Commentary on Romans 2:15.

— Nicholas K. Meriwether is Professor of Philosophy at Shawnee State University in Portsmouth, OH. He has taught the Ethics requirement at SSU for 26 years. He received an MA in Christian Thought from Trinity Evangelical Divinity School, and a PhD in Philosophy from Purdue University. He has published in the areas of moral psychology, Critical Theory, Islamic militancy, and the role of ethics instruction in higher education. He and his wife, Janet, have three grown children. They are members of the Presbyterian Church in America.

Image by David Mark from Pixabay

[sponsored]

Quick answers to tough questions about Jesus' life, ministry, and divinity.

Is there archeological proof that Jesus existed? Did Jesus ever actually claim to be God? Is Jesus really the only way? There's a good chance that every Christian will be asked tough questions like these at some point in their lives, whether from combative skeptics, curious seekers, or even doubts in their own minds.

To help followers of Christ answer questions quickly and confidently, Josh and Sean McDowell adapted the wisdom from their apologetics classic Evidence That Demands a Verdict into an accessible resource that provides answers to common questions about Jesus.

Evidence for Jesus answers these questions and more:

Is there evidence that Jesus was real?

Did Jesus ever actually claim to be God?

What makes Jesus unique from other religious figures?

Is Christianity a copycat religion?

What does the Old Testament teach about the coming Messiah?

Did Jesus really rise from the dead?

Why does the resurrection of Jesus matter?

Evidence for Jesus will equip brand new believers and lifelong Christians alike with time-tested rebuttals to defend their faith in Jesus against even the harshest critics.

See our recent excerpt from Evidence for Jesus on “dying and rising gods” here.

Find Evidence for Jesus at Amazon, FaithGateway, and other major booksellers.

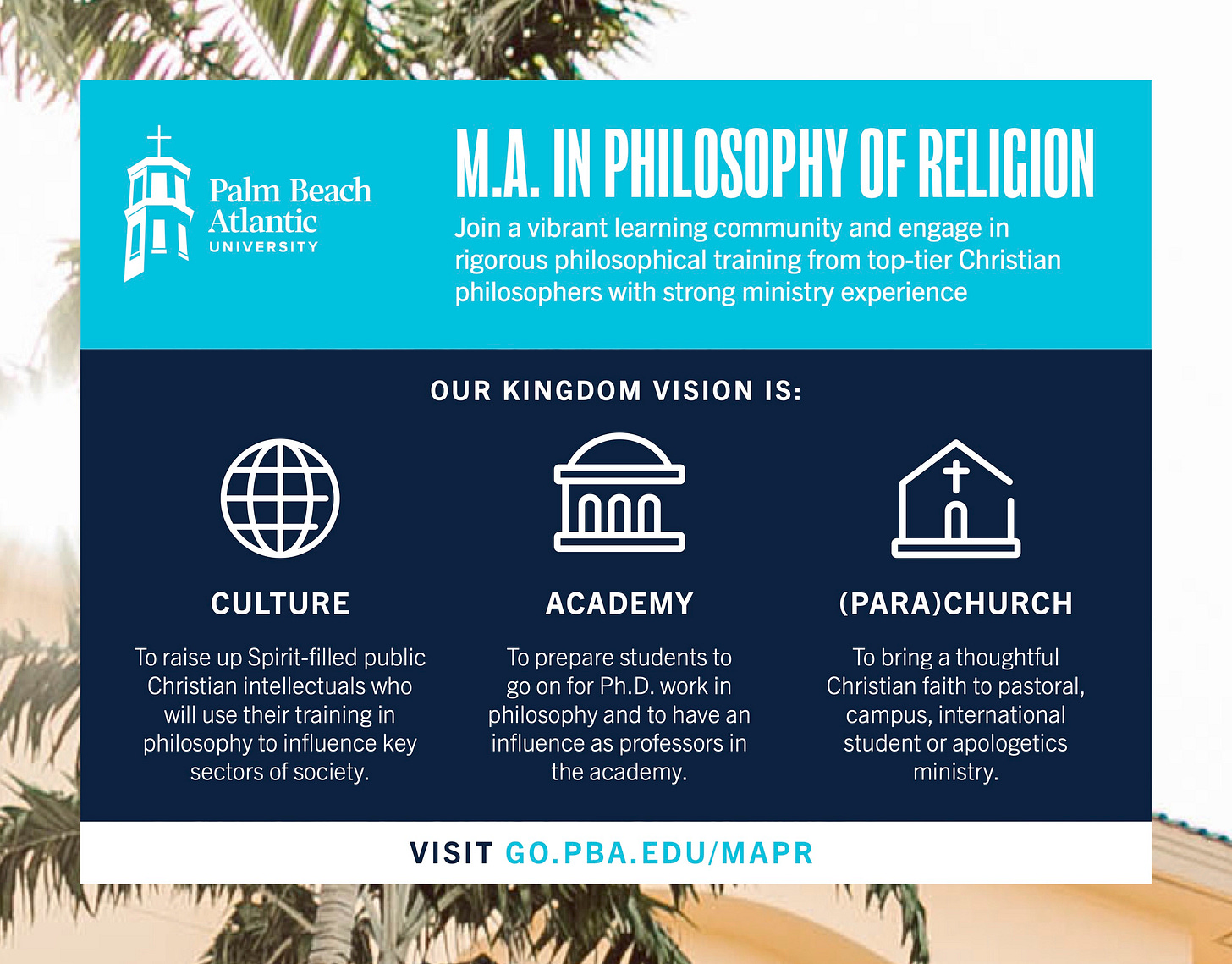

To learn more, visit go.pba.edu/mapr, or email Dr. Paul Gould, Director of the MA in Philosophy of Religion program, at Paul_Gould@pba.edu.

Summit Ministries Student Conferences

Give Your Kids An Unshakeable Faith This Summer

Jeff Myers, Ph.D., President of Summit Ministries

As the president of Summit Ministries, I invite young adults ages 16 to 22 to join the Summit faculty and me to change the trajectory of their lives through two weeks of learning, dialogue, and mentoring in a biblical worldview and cultural engagement.

Thanks to generous donors, I have over $400,000 of financial assistance available for families this summer. I’m looking for students to join us in Lookout Mountain, Georgia, or Manitou Springs, Colorado, for our Student Conferences. As a reader of The Worldview Bulletin, you also receive an exclusive discount using the discount code BULLETIN.

Why Summit and why this summer? Our vision is for a generation that embraces God’s truth and stands against the culture’s lies. After two weeks at Summit, eighty-five percent of students have embraced a biblical worldview, and independent studies show that the change lasts even one, five, and ten years later.

We’re looking for students who will bring their hard questions and a willingness to learn. We will equip them with biblical truth, facts, and the boldness to live with purpose and become leaders.

Over the last 60 years, Summit Ministries’ graduates have become courageous Christians in business, politics, the military, medicine, science, academia, and more.

The times are urgent and call for fearless action. Sessions are filling up quickly. Click to learn more about Summit Ministries summer conferences.

P.S. Through partnerships with Christian colleges and universities, students who attend a 2023 session can receive up to $10,000 in college scholarships and earn up to 3 college credits during their two-week session.

—Dr. Jeff

Jeff Myers, Ph.D., President

Summit Ministries

Divine Love Theory

How the Trinity Is the Source and Foundation of Morality

What if the loving relationships of the Trinity are the ultimate, objective source for living morally?

Adam Lloyd Johnson injects a fresh yet eternal reality into the thriving debate over the basis of moral absolutes. Divine Love Theory proposes a grounding for morality not only in a Creator but as God revealed in the Christian Scriptures—Father, Son, and Spirit eternally loving one another.

Johnson contends that the Trinity provides a remarkably convincing foundation for making moral judgments. One leading atheistic proposal, godless normative realism, finds many deficiencies in theistic and Christian theories, yet Johnson shows how godless normative realism is susceptible to similar errors. He then demonstrates how the loving relationships of the Trinity as outlined in historic Christian theology resolve many of the weakest points in both theistic and atheistic moral theories.

“Johnson leaves no stone unturned, his research is exceptional, and his topic and treatment of it are first-rate. I very strongly recommend this book.”

— J. P. Moreland, distinguished professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology, Biola University

“Johnson’s book is very well done and very helpful to the reader; I love the historical overview. Also, his Evolutionary Debunking Argument against Wielenberg’s position is really good. Lastly, I found the part on imaging the obedience in the Trinity as a basis for the obligation to obey God creative and interesting.”

— William Lane Craig, professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology and Houston Christian University

See our recent excerpt from Divine Love Theory here.