This past summer, where I live and in lots of other places, man and beast had a good reason to avoid going outside: outrageous heat and stifling humidity. My wife and I recently joked we should move to somewhere cooler, like the surface of the sun. Fortunately, I had some writing projects this summer to occupy my time and give me an excuse to remain indoors, but none of us works every waking minute. We neither can nor should. As the summer wore on, I found myself feeling a bit stir crazy and in need of some decompression.

At first nothing about this struck me as much relevant to theology or apologetics. I just started by constructing a list of ways to blow off some steam: watching a television show, an escape room, a game, swimming, walking, going to the gym, sex, praying, reading the Bible, memorizing Scripture, going to a movie, going out to eat, cooking, cleaning, organizing, yoga, studying a language, chatting with a friend or relative, reading a novel or some nonfiction, listening to music, watching a documentary, attending church, participating in a prayer or fellowship group, cultivating a new friendship, mentoring someone, helping another at their point of need, the spiritual disciplines, volunteering, learning a musical instrument, taking a class, journaling/writing, listening to or making a podcast, cuddling, watching or playing a sport, going for a drive, enjoying nature, going to an apple orchard, going to camp meeting, going to an art gallery, sharing one’s faith, enjoying conversation, etc.

Some of these activities are entertainment-focused, others not so much. There is nothing wrong with fitting in some pleasure and entertainment in our lives, though of course it can be overdone. So one of my first thoughts was how to strike the right balance between (say) work and play. My wife and I, like lots of others, recently finished binging the television show Suits. A fun show, it made us laugh quite a bit. But then I read how someone had loved the show so much he binged it seventeen times. Probably not a paradigm of Aristotle’s Golden Mean!

My stepson, Nathaniel, has developed a love of baseball in recent years, and so we’ve started watching Ken Burns’ documentary on baseball when he and I get together. I’d seen it some years ago, but I’m enjoying watching it again with him. It’s dawned on me, while watching it, that baseball, like other games, has this neat feature about it: it’s the sort of thing that would take place even in a perfect world. Wars would cease, but baseball would persist. Or there’s no reason it shouldn’t. I lost my own dad thirty years ago, but I still remember, with more than a little nostalgia, how on summer afternoons and evenings in Michigan he’d tinker in the garage for hours while listening to Ernie Harwell and Paul Carey’s radio broadcast of Tiger games. In retrospect it seems almost magical to think of now, simpler yet somehow profounder times.

Someone in the first hour of the documentary said that there is nothing philosophical about baseball; rather, “it’s just fun.” I get what he’s saying, but the more I think of it, I’m not so sure. It certainly is a beautiful game, and it’s surely fun—to watch or to play—but perhaps not merely fun. In fact, as a Christian, I’m not inclined to see much of anything anymore as “merely” anything. Roger Scruton once wrote the following:

It is helpful . . . to register a protest against what Mary Midgley calls “nothing buttery.” There is a widespread habit of declaring emergent realities to be “nothing but” the things in which we perceive them. The human person is “nothing but” the human animal; law is “nothing but” relations of social power; sexual love is “nothing but” the urge to procreation; altruism is “nothing but” the dominant genetic strategy described by Maynard Smith; the Mona Lisa is “nothing but” the spread of pigments on a canvas; the Ninth Symphony is “nothing but” a sequence of pitched sounds of varying timbre [sic]. And so on. Getting rid of this habit is, to my mind, the true goal of philosophy. And if we get rid of it when dealing with the small things—symphonies, pictures, people—we might get rid of it when dealing with the large things too: notably, when dealing with the world as a whole. And then we might conclude that it is just as absurd to say that the world is nothing but the order of nature, as physics describes it, as to say that the Mona Lisa is nothing but a smear of pigments. Drawing that conclusion is the first step in the search for God.[1]

William James once said that, while the knights of (Ockham’s) Razor fear superstition, he feared desiccation. My Worldview Bulletin colleague Paul Gould has perspicaciously written about the desacralization of the modern world and the need for its re-enchantment. I couldn’t agree more. Cultivating eyes to see the significance of the ordinary and seeming garden-variety is a step in the right direction. Let’s remember that Christianity is the faith that infuses something like a meal with more sacramental significance than we can begin to imagine.

So how might play, of various sorts, be a part of redeeming time and doing all for the glory of God, as we’re instructed to do? For some help to see, consider Christian sociologist Peter Berger’s Rumor of Angels. Another WB colleague and friend, Melissa Cain Travis, has written poignantly about Berger’s “argument from damnation.” That was one of five such arguments of which Berger wrote. The others were arguments from order, hope, humor, and, most relevant for present purposes, play. Perhaps we’ll have other occasions to discuss the others some more, but for now let’s think about the argument from play. All five of these arguments are what Berger called “signals of transcendence,” a phrase with which most readers are likely already familiar.

Signals of transcendence are, on Berger’s account, more signs of something than proofs. They hint and intimate at deeper significance. Berger was writing at a time when he saw the need to use such arguments with a soft touch, to invoke pieces of evidence that speak in the seemingly ordinary experience of life. For those with eyes to see, they may well contain more. He thought such a grounded approach might serve as a partial corrective to the growing cynicism and deflationism of his day and some protection against the incessantly fluctuating winds of cultural moods.

Play, to begin with, sets up a separate universe of discourse and its own rules. “In playing, one steps out of one time into another.”[2] Moreover, “Joy is play’s intention. When this intention is actually realized, in joyful play, the time structure of the playful universe takes on a very specific quality—namely, it becomes eternity.”[3] It’s this curious quality, moving us from time to eternity, a reprieve from life’s challenges and scarier trajectories, that explains the liberation and peace that play provides. This is often unconscious in children, whereas in play among adults, “they momentarily regain the deathlessness of childhood,” even in the face of acute suffering and dying. This is what stirs us about men making music in a city under bombardment or a man doing mathematics on his deathbed.[4]

C. S. Lewis, at the beginning of World War II, wrote about this eloquently: “Human life has always been lived on the edge of a precipice…. Men … propound mathematical theorems in beleaguered cities, conduct metaphysical arguments in condemned cells, make jokes on scaffolds, discuss the last new poem while advancing to the walls of Quebec, and comb their hair at Thermopylae. This is not panache; it is our nature.”[5]

Earlier we spoke of balancing work and play, but the picture is actually more textured than that: we can and often do play even in our work. Fred Rogers was wont to say that the work of children is play. I quite agree, and might add that it continues to be the work of adults, and that our work should always aim to incorporate elements of play. In so doing we recapture the unmitigated joy of girls playing hopscotch in the park. For the duration of the game, the outside world has ceased to exist. “Even the adult observer of this scene, who is perhaps all too conscious of pain and death, is momentarily drawn into the beatific immunity.”[6]

The death-refusing hope within us might be thought of as (nothing but!) childish. Or it might instead be seen as a piece of childhood wisdom that recognizes that death is not the way it ought to be: “an affirmation of the ultimate triumph of all human gestures of creative beauty over the gestures of destruction, and even over the ugliness of war and death.”[7] In the reality of ordinary life, experiences of joyful play can function semiotically, pointing beyond themselves to something more ultimate. Berger thought they pointed best to a supernatural justification.

I admit that, rather than tight discursive analyses that are supposed to stymie and silence opponents and beat them into intellectual submission, a thousand quiet echoes and subtle intimations speak to me the loudest nowadays. So there’s something powerful in Berger’s words here I’m drawn to. As he put it, “All men have experienced the deathlessness of childhood and we may assume that, even if only once or twice, all men have experienced transcendent joy in adulthood. Under the aspect of inductive faith, religion is the final vindication of childhood and of joy, and of all gestures that replicate these.”[8]

Notes

[1] Roger Scruton, Soul of the World (Princeton, NY: Princeton University Press, 2014), 39-40.

[2] Peter Berger, A Rumor of Angels: Modern Society and the Rediscovery of the Supernatural (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1970), 58.

[3] A. E. Taylor’s classic Faith of a Moralist has much to say about the timelessness of certain experiences, like listening to a symphony, and what this suggests about the eternal life to which we’re called.

[4] Berger, 59.

[5] C. S. Lewis, The Weight of Glory (Grand Rapids, MI: Eerdmans, 1965), 44ff. Lewis also famously wrote that “it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors. This does not mean that we are to be perpetually solemn. We must play [emphasis added]. But our merriment must be of that kind (and it is, in fact, the merriest kind) which exists between people who have, from the outset, taken each other seriously—no flippancy, no superiority, no presumption.”

[6] Berger, 59.

[7] Berger, 60.

[8] Ibid.

— David Baggett is Professor of Philosophy and Director of the Center for the Foundations of Ethics at Houston Christian University. He is the author or editor of about fifteen books, most recently Ted Lasso and Philosophy: No Question Is Into Touch edited with Marybeth Baggett.

Image by Daniela Dimitrova from Pixabay

[In partnership with our sponsors]

Bridge-Building Apologetics

How to Get Along Even When We Disagree

Bridge-Building Apologetics is about establishing caring and compassionate relationships with those whom you desire to reach for Christ. In this friendly and helpful resource, you will find

inspiring examples of relational apologetics from people in the Bible and modern-day bridge builders

strategies for thoughtful and productive interactions with unbelievers and people of diverse faith backgrounds

practical tips for engaging non-Christians in relationships and faith-centered conversations, with real-life examples.

Going beyond merely comparing truth with error, this accessible and informative guide shows you how to overcome relational barriers and graciously reach out to those with whom you disagree. Even in the face of deep differences, these insights and tips will help you will grow in your confidence to engage others effectively with the love of Jesus and the truth of Scripture.

“After decades of experience in apologetics, I often lament that so many unbelievers are ignorant of apologetics because Christians often lack the intellectual and relational skills needed to bring the case for Christianity to unbelievers. This book is a welcome and much-needed antidote to that problem. Through its use of Scripture, personal experiences, culture, and apologetic savvy, Bridge-Building Apologetics equips Christians to 'contend for the faith that was once for all delivered to the saints' (Jude 3 ESV).”

— Douglas Groothuis, University Research Professor of Apologetics and Christian Worldview at Cornerstone University; author of Christian Apologetics: A Comprehensive Case for Biblical Faith

See our recent excerpt from Bridge-Building Apologetics here.

Find Bridge-Building Apologetics at Harvest House, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Christianbook.com, and other booksellers.

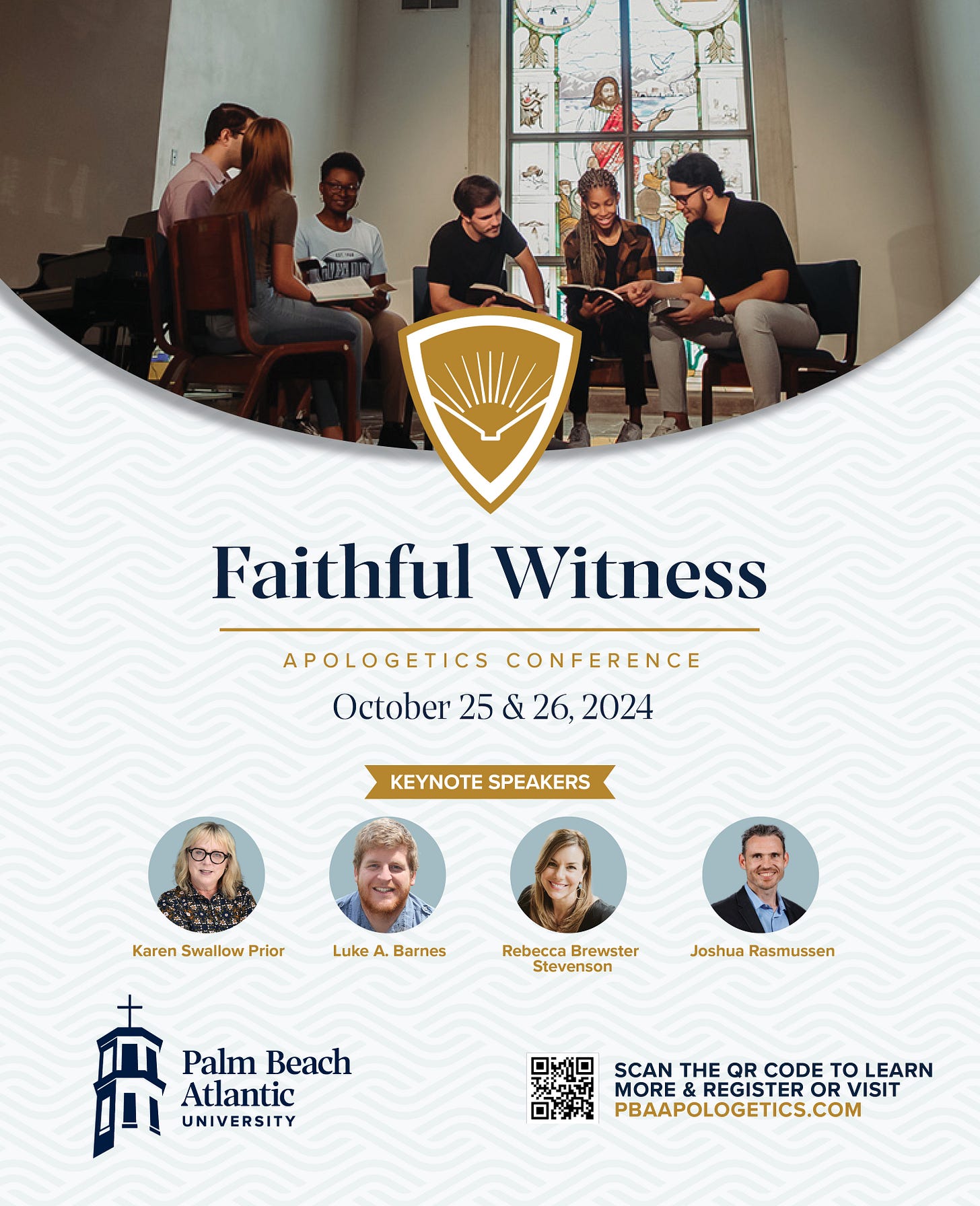

Learn more and register here: https://pbaapologetics.com/pba-2024-apologetics-conference/.

Natural Theology: Five Views

Natural theology is a matter of debate among theologians and Christian philosophers. In this book, top scholars in the fields of theology and Christian philosophy introduce readers to five prevailing views on the topic. Contributors include John C. McDowell, Alister E. McGrath, Paul K. Moser, Fr. Andrew Pinsent, and Charles Taliaferro.

The contributors offer constructive approaches from major perspectives—contemporary, Catholic, classical, deflationary, and Barthian—in a multiview format to provide readers with the “state of the question” on natural theology. Each unit consists of an introduction by a proponent of the view under discussion, responses from the other contributors, and a final response by the proponent. James Dew and Ronnie Campbell provide a helpful introduction and conclusion.

“In this thought-provoking book, leading scholars from five distinct viewpoints come together to discuss key questions concerning natural theology. Through their engaging and insightful dialogue, this volume provides a comprehensive and balanced overview of the subject. It is a must-read for scholars and students of philosophy and theology as well as for anyone interested in exploring the relationship between faith and reason.”

—Yujin Nagasawa, Kingfisher College Chair of the Philosophy of Religion and Ethics, University of Oklahoma

See our recent excerpt from Natural Theology: Five Views here.

Find Natural Theology: Five Views at Baker Academic, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Christianbook.com, and other booksellers.

This November, join Sound Faith Consulting for a two-day event to learn from and engage with the most influential voices defending the Christian faith today. Keynote talks will be given by William Lane Craig, Michael Licona, and J. Warner Wallace. Held at Emmanuel Faith Community Church in Escondido, CA, this event will feature interactive sessions with leading scholars on topics such as God’s existence, the resurrection of Jesus, faith and science, and more. And if you can't make it in person, don't worry! There is a livestream option where you can catch the keynote talks, as well as commentary and interviews by popular YouTubers Ruslan KD and Apologia Center! Get your tickets and schedule information at soundfaith24.com.

Subscribe to The Worldview Bulletin

The Worldview Bulletin thrives when readers subscribe. We defend the truth, goodness, and beauty of the Christian worldview, building up believers and challenging non-believers. Sign up here to access all of our resources and support our work of commending and defending the Christian faith. You can also give a one-time donation here at our secure giving site.

It takes a tremendous amount of time and energy to produce The Worldview Bulletin on a weekly basis, and it’s only possible because of our paying subscribers. If you find value in our work, please consider becoming one or giving someone else a gift subscription.

“The Worldview Bulletin is a must-have resource for everyone who’s committed to spreading and defending the faith. It’s timely, always relevant, frequently eye-opening, and it never fails to encourage, inspire, and equip.”

— Lee Strobel, New York Times bestselling author of more than forty books and founding director of the Lee Strobel Center for Evangelism and Applied Apologetics

“Staffed by a very respected and biblically faithful group of Evangelical scholars, The Worldview Bulletin provides all of us with timely, relevant, and Christian-worldview analysis of, and response to, the tough issues of our day. I love these folks and thank God for their work in this effort.”

— JP Moreland, distinguished professor of philosophy, Talbot School of Theology, Biola University, author of Scientism and Secularism: Learning to Respond to a Dangerous Ideology (Crossway)

Advertise in The Worldview Bulletin

Do you have an educational institution, ministry, book, course, conference, or product you’d like to promote to 7,585 Worldview Bulletin readers? Click here to learn how. We’re currently booking for October-November.

Why the "[sic]" for "timbre"? It's used and spelled correctly. (Yes, it's pronounced "tamber", but it's spelled with an "i" all the same. The "re" at the end is also standard; "timber" isn't an alternative unless you're talking about fallen trees.) This nitpick aside (unless I'm wrong and have the pleasure of learning something new), it's a nice essay.