Should We Read More, or Deeper?

By Rachel B. Griffis, Julie Ooms, and Rachel M. De Smith Roberts

One of the challenges of constructing a syllabus, planning a book club, leading a small group Bible study, or building one’s personal to-be-read pile is the pressure to prioritize reading more—more poems, more pages, more verses—as though glutting ourselves weren’t counterproductive if we also want to read deeply. . . . And the sheer volume of reading possibilities available to us is so staggering that narrowing our attention to smaller chunks of text might seem unambitious (at least) or a grim reminder of our own inevitable deaths (at most). In The Common Rule, Justin Earley describes the experience of standing in awe inside a jam-packed bookstore and realizing, after some quick mental math, that at his current reading rate, he had enough years left to read 1,500 more books in his lifetime, give or take. “That’s when I had a realization of my mortality. My desire outpaced reality. I simply didn’t have the life to read what I wanted to read,” Earley concludes. To further our gastrological metaphor here: Earley’s eyes were bigger than his stomach. And most of us know the overstuffed feeling of having eaten more than we could comfortably digest: instead of nourished and energized, we feel sick and sluggish.

Being confronted by our own mortality is hardly a comfortable position to be in, either, and few of us want to confront it at all, let alone as we read a syllabus or eye the stack of books on our nightstand. [Our] technologies often provide a false antidote for the reality of our limitedness. In allowing us a seemingly unbounded reach across space and an unfathomable amount of content for our consumption, these technologies lead us to think that our minds, like an AI chatbot consuming digital reams of written material in order to “learn,” can “take in information the way the Net distributes it: in a swiftly moving stream of particles” that transform us from “a scuba diver” plunging deeply into a “sea of words” into a jet skier “zip[ping] along the surface.” Or, as Sven Birkerts describes in The Gutenberg Elegies, when we are “awed and intimidated by the availability of texts, faced with the all but impossible task of discriminating among them,” we “tend to move across surfaces, skimming, hastening from one site to the next without allowing the words to resonate inwardly.” But we are not machines, and we do not have a limitless capacity to shallowly and speedily consume texts—nor should we desire such a capacity. Instead, what we want to cultivate is a capacity to savor smaller bites so that they “resonate inwardly” and truly nourish us.

To that end, we recommend spending at least a handful of class days, club meetings, or personal reading hours on smaller chunks of text, such as single poems, a handful of verses, or one piece of a scholar’s argument. For example, in an American Literature class, my students and I (Ooms) spend a whole class period discussing a handful of Emily Dickinson poems. Before our class meeting, I ask my students to choose three Dickinson poems from our anthology that they want to discuss. During our class meeting, students share their choices, and we usually end up focusing our class meeting on three or four poems. Memorably, one semester, we spent twenty minutes discussing a four-line poem:

“Faith” is a fine invention For Gentlemen who see! But Microscopes are prudent In an Emergency!

These brief lines had caught more than one of my students’ attention and held it. . . . Part of our discussion focused on Dickinson’s humor here, which comes across clearly even in only four lines. We discussed ways of interpreting the italicized word “see” as well as Dickinson’s capitalization choices. These twenty minutes were rich; we very much savored this poem and the handful of others we discussed during this class period. Diving deep into this poem rather than skimming across the surface of many Dickinson poems helped my students temper their powers of attention and allow the poem to resonate within and among them.

— Rachel B. Griffis is associate professor of English at Spring Arbor University in Spring Arbor, Michigan.

— Julie Ooms is associate professor of English at Missouri Baptist University in St. Louis, Missouri.

— Rachel M. De Smith Roberts is associate professor of English at North Greenville University in Tigerville, South Carolina.

Image by Mircea Iancu from Pixabay

---

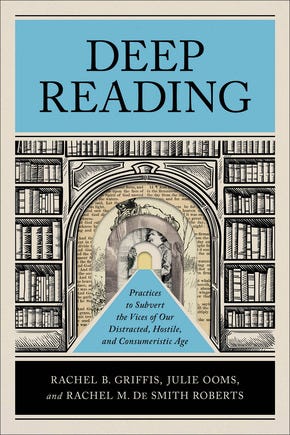

Excerpted from Deep Reading: Practices to Subvert the Vices of Our Distracted, Hostile, and Consumeristic Age by Rachel B. Griffis, Julie Ooms, and Rachel M. De Smith Roberts (Baker Academic, 2024). Used by permission.

“Deep Reading ought to be read and wrestled with by all those who want to read carefully and well, and it's particularly essential for those tasked with guiding others' reading in the classroom, the church, or the home. With its wealth of creative and practical examples, this book will enliven our efforts to read redemptively.”

— Jeffrey Bilbro, associate professor of English, Grove City College

“Drawing from years of experience and research, Deep Reading offers insights, approaches, and practices to equip readers and teachers of readers. The book not only instructs—it inspires. I wish I had this work when I began teaching thirty years ago. It's not only a book for teachers; it's a book for all readers who desire to read deeply and to live deeply as well.”

— Karen Swallow Prior, author of The Evangelical Imagination: How Stories, Images, and Metaphors Created a Culture in Crisis

Find Deep Reading: Practices to Subvert the Vices of Our Distracted, Hostile, and Consumeristic Age at Baker, Amazon, Barnes & Noble, Christianbook.com, and other booksellers.

*sponsored

I ask the Holy Spirit to guide my reading and it's amazing what falls into my lap.

This is exactly why I am reading the NT book of Matthew in small bites, responding in small chunks of writing (for future publication). More time for mulling and processing...and hopefully remembering and applying.